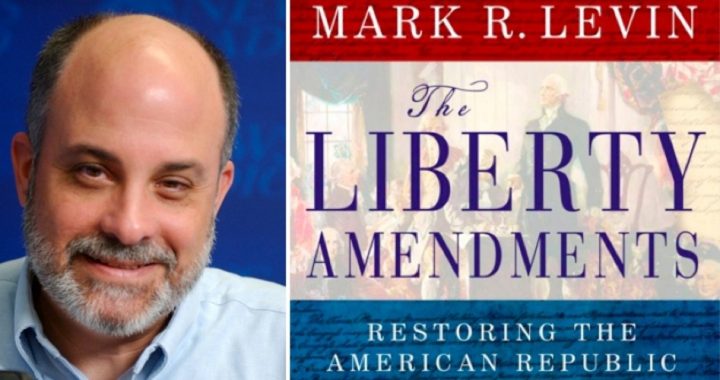

The Liberty Amendments: Restoring the American Republic, by Mark R. Levin, New York, N.Y.: Threshold Editions, 2013, 272 pages, hardcover.

When talk-show host Mark Levin’s latest book, The Liberty Amendments, was released to the public in mid-August, its rapidly spreading impact among the despairing conservative throngs resembled the effect of dropping a lighted match on great quantities of dry tinder. The rapidly developing impact was greatly enhanced by the endorsement of Levin’s proposal for an Article V constitutional convention by three of the most popular conservative talk-show hosts, Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, and Levin himself.

It is very apparent that this national phenomenon is due to the book’s provision of a program of action that promises to rein in the federal government. In a nutshell, Levin’s solution to our out-of-control federal government involves: (1) getting an Article V convention for proposing amendments (popularly known as a “constitutional convention”) convened, as discussed in chapter one; and (2) getting some amendments proposed (and sent to the states for ratification) at such a convention to address the problem of an out-of-control federal government, such as his 11 amendment proposals as discussed in chapters two through 11. Since we disagree with his proposal for an Article V convention, we won’t be spending much time on the 11 amendments; however, we definitely agree with him that repealing the 17th Amendment would be a good idea.

During a whirlwind review in chapter one of the seemingly endless ways in which the federal government is departing from the Constitution, Levin accurately observes:

Having delegated broad lawmaking power to executive branch departments and agencies of its own creation, contravening the separation-of-powers doctrine, Congress now watches as the president inflates the congressional delegations [of power to the executive branch] even further and proclaims repeatedly the authority to rule by executive fiat in defiance of, or over the top of, the same Congress that sanctioned a domineering executive branch in the first place.

A Constitutional Convention?

A few pages later, Levin reveals that his solution to this problem of an out-of-control federal government is to amend the Constitution by utilizing the provision in Article V for convening “a Convention for proposing Amendments” based on the direct application to Congress of two-thirds of the state legislatures.

At this point he takes a little preemptive shot across the bow of the numerous constitutionalists who have been opposing such a convention over the past 30 years by quoting Article V with its two methods for amending the Constitution (via Congress or via a convention called by the state legislatures), then stating: “Importantly in neither case does the Article V amendment process provide for a constitutional convention.”

At this point he takes a little preemptive shot across the bow of the numerous constitutionalists who have been opposing such a convention over the past 30 years by quoting Article V with its two methods for amending the Constitution (via Congress or via a convention called by the state legislatures), then stating: “Importantly in neither case does the Article V amendment process provide for a constitutional convention.”

This type of comment has become a standard semantic weapon in the arsenal of the pro Article V convention forces. However, both conservatives and liberals have routinely referred to an Article V “Convention for proposing Amendments” as a “constitutional convention” for well over 30 years, and likely much longer. And they haven’t done this because they mistakenly believe that the words “constitutional convention” are to be found in Article V.

For example when the Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution of the Committee on the Judiciary held a hearing on November 29, 1979, regarding the role of Congress in calling an Article V convention, the official name of the hearing as published by the Government Printing Office in a 1,372-page document was “Constitutional Convention Procedures.” This hearing was held because the number of states petitioning Congress to hold an Article V convention to propose a balanced budget amendment was rapidly approaching the necessary 34 states.

The reason Levin and other pro-convention forces want to deny the validity of the phrase “constitutional convention” in this context is that one of the most persuasive arguments against holding such a convention is based on the contention that such a convention could become a “runaway” convention based either on the inherent nature of “constitutional conventions” or on what transpired at our original “Constitutional Convention” in 1787.

Since respect for our Constitution has been so widespread, state legislators have been very reluctant to approve calls for a constitutional convention that could lead to harmful changes in the Constitution.

Levin correctly observes in chapter nine:

It is undeniable that the states created the federal government and enumerated its powers among the three separate branches; the states reserved for themselves all governing powers not granted to the federal government; and the Constitution they established enshrined both.

This observation leads to the topic of “extra-constitutional” powers of states regarding the federal government, as implied by the compact theory of the union so aptly summarized by Levin in the above quote. Although Article V of the Constitution provides for a constitutional convention to be called by the states, the people of the states already have the extra-constitutional right to convene a constitutional convention by virtue of the Declaration of Independence.

Take a careful look at this passage in the early portion of the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

You can break this passage down into three parts: (1) Our rights come from God; (2) governments, such as our present federal government as defined by the Constitution, are instituted to secure our rights; and (3) whenever any form of government fails to secure our rights, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government.

Therefore the state convention method of amending the Constitution as provided in Article V can be seen as the Founders’ way of incorporating into the Constitution the Declaration’s “right of the people to alter or to abolish” our government whenever it fails to secure our rights.

This right is referred to as the theory of popular sovereignty. Moreover, this theory wasn’t just specific to Jefferson’s thinking. It was a consensus notion among the Founding Fathers. Consider for example what Edmund Pendleton, president of the Virginia ratifying convention, said to the delegates on June 5, 1788:

We, the people, possessing all power, form a government, such as we think will secure happiness: and suppose, in adopting this plan, we should be mistaken in the end; where is the cause of alarm on that quarter? In the same plan we point out an easy and quiet method of reforming what may be found amiss. No, but, say gentlemen, we have put the introduction of that method in the hands of our servants, who will interrupt it from motives of self-interest. What then?… Who shall dare to resist the people? No, we will assemble in Convention; wholly recall our delegated powers, or reform them so as to prevent such abuse; and punish those servants who have perverted powers, designed for our happiness, to their own emolument.

Although there are some ambiguities in this passage, Pendleton appears to be assuring the delegates that if the Constitution turned out not to secure happiness for Americans, then it could be reformed by the “easy and quiet” methods of Article V. However, if the Article V process were to be subverted by “our servants,” the state and federal legislators, then We the People (the sovereign people) would assemble in convention, wholly recall and reform the delegated powers of the Constitution, and punish the offending servants.

Runaway Convention

Now back to Levin’s line of reasoning. On page 15 Levin states:

I was originally skeptical of amending the Constitution by the state convention process. I fretted it could turn into a runaway convention process…. However, today I am a confident and enthusiastic advocate for the process. The text of Article V makes clear that there is a serious check in place. Whether the product of Congress or a convention, a proposed amendment has no effect at all unless “ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several States or by Conventions in three fourths thereof….” This should extinguish anxiety that the state convention process could hijack the Constitution.

In this quote Levin admits that he shares the concerns of others that an Article V convention could turn into a “runaway convention,” but asserts that he has overcome those concerns with his belief that “Article V makes clear that there is a serious check in place,” namely the requirement of ratification of amendments by three-fourths of the states. There are several reasons why Levin should not be so assured that this is a “serious check” in place to stop a runaway convention.

First, the ratification by three-fourths of the states requirement of Article V already has failed to prevent undesirable amendments from being ratified. Consider the 16th Amendment (income tax), the 17th Amendment (direct election of senators), and the 18th Amendment (prohibition). All three were ratified by at least three-fourths of the states, but most constitutionalists would likely agree that all three were bad amendments and should not have been ratified. In particular, many constitutionalists think that changing the method of choosing U.S. senators from appointment by state legislatures to direct election by the voters in each state as provided by the 17th Amendment has been extremely damaging to our constitutional republic.

Second, it is hard to predict just how much pressure could be brought to bear on the American public and state legislators or state convention delegates to get some future undesirable amendment or amendments ratified by the three-fourths rule.

Third, it is quite possible that an Article V constitutional convention would specify some new method of ratification for its proposed amendments. After all, our original Constitutional Convention in 1787, an important precedent for any future constitutional convention, changed the ratification procedure for the new Constitution from the unanimous approval of all 13 state legislatures required by the Articles of Confederation to the approval by nine state conventions in Article VII of the new Constitution. Furthermore, as discussed above, the extra-constitutional “right of the people to alter or to abolish” our government whenever it fails to secure our rights, as proclaimed by the Declaration of Independence, would certainly encompass altering the method of ratification for any new amendments that might result from an Article V constitutional convention.

But not to worry, Levin has another method for assuaging our concerns about a runaway convention. On page 16 he quotes from Robert G. Natelson, a former professor of law at the University of Montana:

[An Article V] convention for proposing amendments is a federal convention; it is a creature of the states or, more specifically, of the state legislatures. And it is a limited-purpose convention. It is not designed to set up an entirely new constitution or a new form of government.

Levin is using this quote from Natelson to assure us that an Article V convention would be a very limited convention. We’re led to think that such a convention wouldn’t hurt a flea — that there’s nothing to worry about from such a meeting.

On the other hand, on page 1 Levin has created a powerful specter of the oppression we live under:

The Statists have been successful in their century-long march to disfigure and mangle the constitutional order and undo the social compact…. Their handiwork is omnipresent, for all to see — a centralized and consolidated government with a ubiquitous network of laws and rules actively suppressing individual initiative, self-interest, and success in the name of the greater good and on behalf of the larger community. Nearly all will be emasculated by it, including the inattentive, ambivalent, and disbelieving.

And, how does Levin propose to deliver us from our bondage under this powerful, totalitarian system of government? His answer is on page 18:

We, the people, through our state legislatures — and the state legislatures, acting collectively [through the state convention process] — have enormous power to constrain the federal government, reestablish self-government, and secure individual sovereignty.

So, Levin is telling us that we “have enormous power to constrain the federal government, re-establish self-government, and secure individual sovereignty” by resorting to (surprise) the “limited-purpose” state convention process, a process that wouldn’t hurt a flea! Obviously Levin believes that Article V conventions do have enormous power, but on the other hand also knows that he must minimize the power of such conventions in order to convince skeptical grassroots Americans to support his constitutional convention proposal.

In other words, constitutionalists can agree that Levin is accurately describing our problems with the federal government; however, many constitutionalists will also agree that Levin is encouraging Americans to play with fire by promoting a constitutional convention. Just because the Constitution authorizes Article V conventions to amend the Constitution doesn’t mean that it would be wise at this time in our nation’s history to call one.

While pro-Article V convention enthusiasts tell us that this is a great time for an Article V convention because the Republican Party controls 26 of the 50 state legislatures (the Democrats control 18, five are split, and one is non-partisan), and therefore could surely block the ratification of any harmful amendments proposed by an Article V convention, they are omitting from this analysis that very many of the Republican state legislators are not constitutionalists, and could end up in alliance with Democrats to ratify some harmful amendments. Not to mention the likelihood that constitutionalists would be in the minority at the convention for proposing amendments itself.

Populism

Now, let’s move on to another area of concern. Levin is proposing an Article V constitutional convention, or as he prefers to call it, “a convention for proposing amendments” or “the state convention process,” as a means to an end. What is his goal? As his book’s subtitle proclaims, his goal is “restoring the American Republic.” Then, on page 6 Levin states: “It is time to return to self-government, where the people are sovereign and not subjects and can reclaim some control over their future rather than accept as inevitable a dismal fate.” (Emphasis added.)

This is a sentence that is easily taken lightly during a first reading of the book, but that assumes a much greater significance when taken in the context of the 11 amendments Levin proposes in chapters two through 11. This sentence expresses a populist solution to our problem of an out-of-control federal government, which helps explain the rapid acceptance of Levin’s proposals. Levin is offering long-suffering conservatives an action plan for grabbing the levers of power over the federal government away from the overbearing elected and appointed officials of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. I’m using “populist” here to refer to a political program to base public policy on the desires of the “sovereign people” of the nation, as in a democracy, rather than on constitutional provisions, as in a republic.

For example, his “Amendment to Grant the States Authority to Directly Amend the Constitution” in Chapter 9 would provide for the states, acting entirely without reference to Congress, to adopt amendments to the Constitution by a two-thirds vote of the state legislatures. This amendment would lower the bar for getting new amendments ratified from the “three-fourths vote of the states” requirement of Article V to just a “two-thirds vote of the state legislatures.” While this difference might seem small, it would still be a move in the direction of democracy and away from a republic, since it is a step in the direction of making it easier for the “sovereign people” to change our Constitution as expressed in this case by a vote of the state legislatures. Such steps are supported by many present-day populists who are also promoting Article V constitutional conventions as steppingstones to the participatory democracy they are working toward. We’ll return to this topic later.

Next, let’s consider Levin’s proposed “Amendment to Grant the States Authority to Check Congress” in Chapter 10. The key provision is “Section 3: Upon three-fifths vote of the state legislatures, the States may override a federal statute.” If this proposed amendment were added to the Constitution, then a three-fifths (60-percent) vote by the state legislatures would veto a law passed by Congress without reference to its constitutionality, another step toward rule by the “sovereign people” (democracy) and away from rule in accordance with the Constitution (republic). Of course, the progressive populists among us would prefer to overturn federal laws by a majority vote of the entire U.S. population without reference to constitutionality, but Levin’s proposed amendment would be a step in the populist direction.

Rounding out this discussion of how Levin’s amendments would empower the state legislatures to grab the levers of power over the federal government away from the elected and appointed officials of its three branches, in the amendment just discussed Levin includes a provision for state legislatures to override certain executive branch regulations, and in his “Amendment to Establish Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices and Super-Majority Legislative Override,” he provides for states to override a majority opinion rendered by the Supreme Court, again (in both cases) without reference to constitutionality.

Related to this discussion of Levin’s populist tendencies is the strikingly small number of mentions of the enumerated powers of the Constitution or the 10th Amendment in this book. However, this makes sense when you realize that the 10th Amendment and the enumerated powers are closely related. Simply stated, the 10th Amendment reserves to the states “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution.” However, Levin’s amendments empowering the states to override the laws, regulations, and legal decisions of the various branches of the federal government make no reference to the powers delegated by the Constitution, a dramatic downgrading of the enumerated powers and the 10th Amendment.

Instead of upholding the Constitution originally ratified by the states in 1788, Levin is creating a mechanism for state intervention in the workings of the federal government that vetoes federal laws, regulations, and legal decisions based on the momentary preferences of the sovereign people as expressed in votes of the state legislatures without reference to the Constitution. For example, imagine a situation where constitutionalists were successful in creating sufficient grassroots pressure to get Congress to pass and the president to sign a law to delete the “indefinite detention” provisions from one of the recent National Defense Authorization Acts based on the unconstitutionality of those provisions. Then imagine that Levin’s “Amendment to Grant the States Authority to Check Congress” was in effect, and that 30 state legislatures, influenced by a sudden outpouring of support for the indefinite detention provisions (as whipped up by the media) among the populations of their states, voted to veto that law. This would be a case where a federal law, based solidly on the Constitution, could be vetoed by 30 state legislatures, based on the presumed will of the sovereign people.

In contrast to Levin’s proposals, a better policy would be for the states, as the original agents who agreed to the compact between the states as spelled out in the Constitution, to enforce (through state nullification of unconstitutional federal laws, for example), not revise, the Constitution.

While we’re considering the populist aspects of Levin’s proposal for a constitutional convention, this is a good time to take a brief look at the populist lovefest, better known as the Harvard Conference on the Constitutional Convention, held at Harvard on September 24-25, 2011, and cosponsored by the Harvard Law School and (surprisingly) the Tea Party Patriots. Of course, Levin’s Liberty Amendments hadn’t been published yet, so the people at Harvard and the Tea Party Patriots didn’t realize that they were using a forbidden phrase, “constitutional convention,” to refer to an Article V convention.

It’s very enlightening to watch videos of the various panels at the Harvard conference. The Harvard host, Professor Lawrence Lessig, and the moderator of the Closing Panel, Richard Parker, wore their populism on their sleeves. Lessig is a left-wing populist and Parker is a plain-old populist (who happens to trace his political lineage back to the 1960s organization, Students for a Democratic Society). They want America to become more and more a democracy with more and more things decided by popular vote. And, they think that holding Article V constitutional conventions will help get them where they want to go. Do they know something that Mark Levin doesn’t know? Watching the online videos of this Harvard conference is a good way to learn why holding a constitutional convention would open Pandora’s box.

The Constitutionalist Strategy

Now, let’s consider the contrasting viewpoint on restoring the American republic. The traditional constitutionalist position, as exemplified by The John Birch Society for over 50 years, is to work to restore our Republic by educating the electorate sufficiently to get a constitutionalist majority elected on the local, state, and national levels. The goal is to bring about adherence by public officials to the Constitution as originally intended by the Founding Fathers.

One of the constitutionalist strategies for reining in our out-of-control federal government is state nullification of unconstitutional federal laws based on the enumerated powers of the Constitution and the 10th Amendment. When approved by a fair number of state legislatures, nullification laws protect the citizens of those states from unconstitutional federal laws and regulations, and whether approved or not, state nullification initiatives educate the electorate about the importance of upholding the Constitution as originally intended.

Our problem of an out-of-control federal government is due to ignorance about the Constitution among the electorate. The solution is to educate the electorate and enforce the Constitution, not to change or ignore it. As Robert Welch, founder of The John Birch Society, was fond of saying: “There is no easy way.”

(Click here for a PDF of this article as it originally appeared in The New American for October 7, 2013.)

Graphic at top: Photo of Mark Levine: AP Images; detail of book “The Liberty Amendments”

This article is an example of the exclusive content that’s only available by subscribing to our print magazine. Twice a month get in-depth features covering the political gamut: education, candidate profiles, immigration, healthcare, foreign policy, guns, etc. Digital as well as print options are available!