The Long Walk has been re-published to coincide with the movie’s limited release, and chronicles the journey of seven prisoners who escape the horrors of a Soviet communist gulag. Their 1941 flight from Siberia ends 4,000 miles and one year later in India, and tells the story of the indomitable human spirit, the will to live, and ultimately the Christian faith that sustains them. More than just a survival story, the book depicts man’s hunger for freedom.

The Way Back departed from the book in some details and sequences of events, and even manufacturers some scenes and story lines. Nonetheless, it captures the same brutal conditions of survival and the escapees’ courage and humanity as depicted in the book.

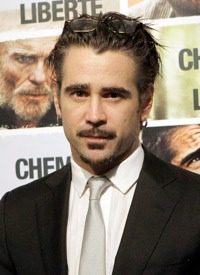

It begins with a Polish soldier named Janusz, played by Jim Sturgess, who is imprisoned for being a spy. The film references his crime as “58," also graphically described in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book The Gulag Archipelago. Early in the film, the newly arrived prisoners are warned that the weather is their real prison, as no one could survive in Siberia if he escaped, but Janusz immediately begins to look for an opportunity. He assembles a small group of willing convicts, they hoard food and some meager tools, and eventually make their break in April of 1941. The multi-national group includes a knife-wielding Colin Farrell (photo above) and, the eldest of the crew, an American played by Ed Harris, who displays his Yankee independence in an act of defiance to the prison guards. Between the seven escapees, they combine languages, woodsmen’s skills, and courage, but they have little else to sustain them.

The landscape, depicted by magnificent cinematography, is its own character. The savage weather and cruel conditions are enemies as much as the fear of recapture. The troop become captives of the environment and endure hypothermia, starvation, ice, drought, dehydration, torturous mosquitoes, and near-madness as they push themselves southward.

Along the way their number is increased by the addition of a young Polish girl, who is also a fugitive from the work camps. Initially, they are reluctant to let her join them, thinking she will only slow them down. The American, called Smith, is especially opposed to allowing her to tag along, but relents when the others cannot leave her to starve. In the end, he becomes more attached to her than anyone else. She displays courage and a spirit of joy, and adds a sense of cohesiveness as she softens their masculine silence, and elicits information about each man that none of the others knows. An endearing feature of the film is the respect for womanhood displayed by all the men. They treat the waifish girl with respect, offer protection, and come to feel a tender affection for her.

The film is replete with Christian symbolism. When the inevitable, death, occurs, a Christian burial is provided, and references to Christian principles, such as gratitude and forgiveness, drive the film. While crossing the Gobi desert, for instance, the group happens upon an oasis. They had been many days without water, and had they not chanced upon it, they would surely have died. The life-giving water relieves their wretchedness and as the sun sets on the scene, their walking sticks are seen forming a large cross at the site of the well.

The director’s choice in depicting the seemingly insurmountable topography, along with lengthy stretches of silence between characters, brings the viewer along into the expanse of woods and desert and endless mountain ranges and into the insufferable monotony of their journey. Mile after mile after mile, they endure horrific and desperate conditions.

The personalities of the characters, however, provide moments of humanity and humor to the story. One of the escapees, an artist, provides his fellow travelers with drawings. Another dreams of salt, and his fixation on it in his waking hours reminds the viewers of their deprivations. There is even a moment of humor as they kill and eat a snake, and they are the recipients of great kindnesses from the few other humans they encounter. The story is singular, too, in that the group does not exhibit conflict, but rather acts as a tightly knit unit trying to help each other.

The portrayal of communism is that of a failed, evil, and barbaric system. The prisoners’ willingness to face ferocious privations in order to find freedom and life is testimony to the worldview presented in both the book and movie. The film ends with the group’s arrival in India, and shows their great joy and relief. Victory is palpable to the viewer, along with a sense of the miracle of deliverance.

The story has only two instances of rough language, and bawdy drawings of women, but it’s PG-13 rating is earned as much by the intensity of the story. It has rough patches unsuitable for young or sensitive viewers, such as a scene in which the starving travelers fall upon some carrion they have wrested from wolves. But it is well cast with believable characters, and is mesmerizing. In the end it is enthralling, masterfully filmed, and an uplifting testament to faith and the gift of freedom. The two hour-and-13-minute investment in The Way Back is well rewarded.