When Chairman Darrell Issa’s House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform was finally able to wade through some 120,000 pages of documents pertaining to Countrywide Mortgage’s special VIP loan program, it came up with some surprising results: the former chairman of that same committee, Representative Edolphus Towns, (D-N.Y.) was on the list of those receiving special treatment. That may have explained why the committee had so much trouble in obtaining those documents in the first place: Towns stalled in issuing the initial subpoena.

In the report, Issa noted that the subpoena was issued only “after several months of resistance” from Towns, adding in a statement to the Associated Press on August 22 that “it was a long fight to expose how Countrywide used its VIP program to advance its business and policy goals.”

Investigative journalist Larry Margasak, who has been following the investigation from the beginning, explained that Towns not only had little interest in exposing his own “hand in the till,” he also wanted to keep his own committee from exposing others also partaking of the VIP program’s “special treatment” through Countrywide. Explained Margasak:

The procedure to keep the names secret was devised by Rep. Edolphus Towns, D-N.Y. In 2003, the 15-term congressman had two loans processed by Countrywide’s VIP section, which was established to give discounts to favored borrowers.

The effort at secrecy was reversed when Towns’ Republican successor as chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, California Rep. Darrell Issa, issued a second subpoena. It yielded Countrywide records identifying four current House members, a former member and five staff aides whose loans went through the VIP unit.

Towns was on the list.

The VIP program developed by Countrywide was designed specifically to influence legislation favorable to the mortgage giant’s interests. The committee report said:

Documents and testimony showed Countrywide used the VIP loan program as a tool to create a favorable impression of the company on Capitol Hill. The documents also showed that senior Countrywide officials and lobbyists explicitly weighed the value of relationships with certain potentially influential borrowers against the cost to Countrywide in terms of forfeited fees and payments.

Some 18,000 loans were processed under Countrywide’s VIP program, including “members of Congress, the White House, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, federal agencies, and other government entities.” The report examined in detail just how deep into the trough Towns was:

In July 2003, Towns applied for a loan to finance the purchase of a home in Lutz, Florida. In an e-mail with Subject “Important Customer,” Stephen Brandt instructed VIP Account Executive Americo Salazar to contact Towns at his office in Washington.

Salazar spoke with Towns. He subsequently notified the VIP processing team that Towns’s credit score might be an issue. Salazar explained that the “Anthrax ordeal in the Capital” prevented Towns from paying bills mailed to his Washington office on time.

Countrywide Underwriter Gene Soda responded to Salazar. He stated that “the credit shouldn’t be a problem.” He added that because “this is a Congressman, we must get his 3 day package out on time.”

When he refinanced his vacation property, Towns received an $182,972, 30-year adjustable rate mortgage starting at 4.50 percent.

Less than a month later, in the summer of 2003, Towns obtained a 30-year, $194,540 mortgage for his Brooklyn residence. Salazar and the VIP unit also handled that loan. Even though Towns identified “US Capital (sic)” as his employer on loan applications for both the Brooklyn and Florida properties, documents show that the VIP unit was aware of Towns’ position as a Member of Congress.

And yet, when Towns was asked about the special treatment he had received from Countrywide, he denied knowing anything about the program, and that he “received no benefits that were not available to everyone else.”

This was just one more effort by Towns to milk the system for his own personal benefit. During his first term as congressman from Brooklyn, Towns was videotaped taking $1,300 in cash from undercover police officers who were posing as businessmen seeking help with federal contracts.

Ten years later, Towns got caught up in the House banking scandal — “Rubbergate” — where he wrote 408 hot checks on the House Bank and left the bank holding the bag on his overdrafts for 18 months. The House Ethics Committee singled out Towns along with 21 other members of the House for special criticism.

Towns continues to milk the system. The New York Post noted that taxpayers are overpaying for a lease on an automobile driven by Towns. The automobile, a Mercury Milan hybrid, has a retail price of $28,180, and Towns is leasing it for $1,285 a month for two years. In simple math, taxpayers will have more than paid for the automobile in that two years, but when questioned about the matter, Towns’ spokesman Julian Phillips said simply: “It is what it is. When he leases his new car, it will be less expensive than this, I’m sure of it.”

By that time, it really won’t matter. In April, Congressman Edolphus Towns announced that he won’t be seeking reelection for his 16th term, leaving his seat open to others eager to dip into the government trough. One of those seeking his place is New York City Councilman Charles Baron, a former Black Panther.

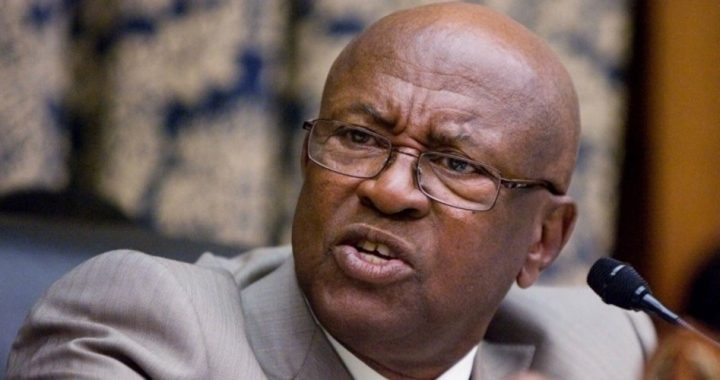

Photo of Rep. Edolphus Towns (D-N.Y.): AP Images