Daily flight logs from Customs and Border Protection (CBP) obtained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation reveal that the federal department has been busy loaning Predator drones to “state, local, and non-CBP federal agencies.”

According to EFF’s summary of the documents, the number of CBP drone flights flown by other organizations has increased “eight-fold between 2010 and 2012.” EFF further reports that “CBP has failed to explain how it’s protecting our privacy from unwarranted drone surveillance.”

CBP calls its report on its Predator surveillance program the “Concept of Operations.” EFF received this report, as well as three years of flight logs, as a result of a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit.

An EFF blog post reports that the Concept of Operations document discloses that “CBP already appears to be flying drones well within the Southern and Northern US borders, and for a wide variety of non-border patrol reasons. What’s more — the agency is planning to increase its Predator drone fleet to 24 and its drone surveillance to 24 hours per day / 7 days per week by 2016.”

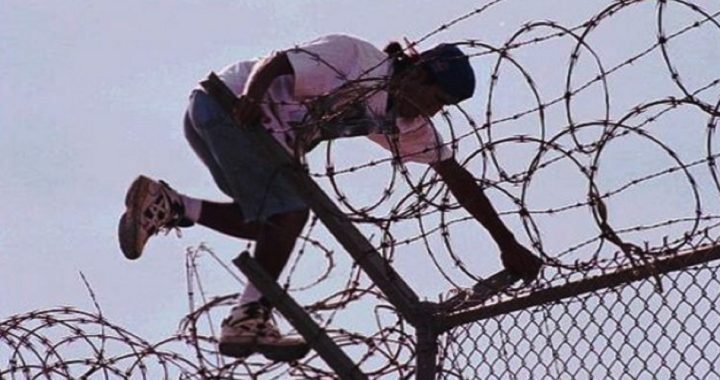

Around the clock, domestic surveillance provided by two dozen Predator drones buzzing in the skies of the United States will, as much as any other federal project, convert the “homeland” into a virtual prison with the inmates under the watchful, never-blinking eye of the wardens.

Just how will the information collected by these unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) be used? The CBP report published by EFF provides some insight:

As the Concept of Operations report notes, CBP’s goal is that its drone data will be “persistently available” (p. 21) and interoperable (p. 29) — not just within CBP, but to other agencies, and also possibly to other countries. CBP plans that its “UAS will provide assured monitoring of entities along land borders, inland seas, littorals and high seas with sufficient frequency, continuity, accuracy, spectral diversity, and data content to produce actionable information.” (p. 29)

While there was much valuable information contained in the cache of documents provided by CBP to EFF, the agency redacted most relevant data related to dates and geographical location of the drone flights. What was revealed, however, was a partial list of the agencies and departments who’ve borrowed CBP’s Predators. The roster includes the FBI, ICE, U.S. Marshals, U.S. Coast Guard, Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Investigation, North Dakota Bureau of Criminal Investigation, North Dakota Army National Guard, Texas Department of Public Safety.

Beyond the law-enforcement purposes behind the drone deployments, EFF reports that “CBP conducted extensive ‘electro-optical, thermal infrared imagery and Synthetic Aperture Radar’ surveillance of levees along the Mississippi River and river valleys across several states, along with surveillance of the massive Deep Water Horizon oil spill and other natural resources for the US Geological Survey, FEMA, the Bureau of Land Management, the US Forest Service, the Department of Natural Resources, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.”

While such activities seem, at first blush, legitimate and not subject to the same scrutiny as more overt surveillance missions, there are collateral aspects of these uses that deserve attention.

Perhaps most critical is the ultimate disposition of the images recorded by the drones deployed on these environmental missions. Photos of rivers, forests, and levees necessarily include pictures of the homes, cars, and other property of people who live in and near these areas. Such surveillance would seem to violate the Fourth Amendment, unless CBP has promulgated standard operating procedures to protect such unwarranted searches.

EFF’s summary of the information it received from CBP also revealed that the agency:

plans to make its drones and the data gathered through its drone surveillance even more widely available to outside agencies. For example, CBP plans to share data on a near real-time basis, possibly “via DOD’s Global Information Grid (GIG)/Defense Information Systems Network.” CBP also plans that “joint DHS and OGA [other government agency] combined operations will become the norm at successively lower organizational hierarchical levels,” which will, presumably, reduce the already limited oversight for CBP’s drone-loan program.

Beginning in 2006, the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) began purchasing its growing fleet of (as yet) unarmed Predator drones. In testimony to Congress, CBP claimed this technology would purportedly aid in securing America’s southern border. According to a report written by the DHS inspector general, as of the end of 2012, CBP will have 12 of these aircraft in its arsenal with a total cost to taxpayers of nearly $200 million.

Inexplicably, the CBP took delivery of two drones in 2011 and 2012 despite the inspector general’s statement that “CBP had not adequately planned resources needed to support its current unmanned aircraft inventory.” So, since they weren’t using the drones they already bought, why not buy more? Although that spendthrift attitude is typical of government agency budgeting, perhaps the purchase of Predators is motivated by a goal a bit more sinister than either DHS or the Obama administration is willing to admit.

These other purposes are even hinted at in the DHS report. The tasks being performed by the CBP drones extend well beyond the patrolling of the border and into many other areas, a situation described by one reporter as “mission creep.” Here is a brief catalog of some of the ways CBP is farming out its drone fleet.

In addition to the borrowers listed in the EFF disclosure, the DHS report indicates that CBP Predators have been used to conduct missions for the following federal and state government agencies:

U.S. Secret Service, … Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); … Department of Defense; Texas Rangers; [and] U.S. Forest Service.

With regard to ICE’s use of the CBP drone, the inspector general’s report indicates that the aircraft “provided surveillance over a suspected smuggler’s tunnel, which yielded information that, according to an ICE representative, would have required many cars and agents to obtain.”

Yes, without the loan-a-drone program, the ICE surveillance mission would have required “many cars and agents,” as well as a warrant. With a drone, the government doesn’t need no stinkin’ warrant.

In a separate report issued in April 2012 by the Department of Defense, the Pentagon revealed the locations of over 100 new domestic sites that could soon serve as launch sites for military drones.

The list of present and proposed drone bases includes 39 of the 50 states, as well as Guam and Puerto Rico.

As for congressional oversight of such serious potential threats to fundamental individual liberties, Representative Ted Poe (R-Texas) has introduced the Preserving American Privacy Act of 2013. Poe’s bill mandates that “in operating a public unmanned aircraft system or disclosing any covered information collected by such operation, a governmental entity shall minimize, to the maximum extent practicable, the collection or disclosure” of “information that is reasonably likely to enable identification of an individual; or information about an individual’s property that is not in plain view.”

On the Senate side, Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) is taking the lead in the fight to prevent unconstitutional surveillance.

On May 22, Paul introduced the Preserving Freedom from Unwarranted Surveillance Act of 2013. This measure protects an individual’s right to privacy against unwarranted drone surveillance.

Paul’s Preserving Freedom from Unwarranted Surveillance Act would reaffirm the right of Americans to be “to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” as guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment.

“The use of drone surveillance may work on the battlefields overseas, but it isn’t well-suited for unrestrained use on the streets in the United States. Congress must be vigilant in providing oversight to the use of this technology and protection for rights of the American people. I will continue the fight to protect and uphold our Fourth Amendment,” Senator Paul said.

Despite these laudable legislative efforts and despite surging international opposition to President Obama’s remote control warfare and death-by-drone program, one of those high-altitude, high-tech, snoop-and-snipe aircraft — owned or loaned by the federal government — may already be flying missions in the skies over the United States.

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American and travels frequently nationwide speaking on topics of nullification, the NDAA, and the surveillance state. He can be reached at [email protected]