The Supreme Court has issued its ruling in the case of McDonald v. City of Chicago. The court found, in a 5-4 vote, that local and state authorities could not effectively ban handgun ownership. The ruling prompted Democratic Senator Diane Feinstein to exclaim that she is “extremely dismayed” because as a result of the ruling “common sense state and local gun laws across the country now will be subject to federal lawsuits.”

While the ruling may make some progressives squirm, the decision handed down by the high court is not a clear-cut win for constitutionalists either, though it does, on balance, represent a victory for the right to keep and bear arms.

Background

Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito noted the court held in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) that “the Second Amendment protects the right to keep and bear arms for the purpose of self-defense.” In that case the court found that the federal District of Columbia could not ban handgun possession in the home. But what about the states?

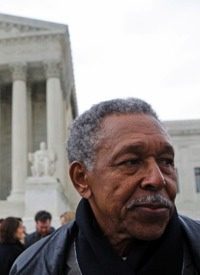

Cities like Chicago have argued, in enacting ordinances that ban possession of guns, that the Second Amendment does not apply to the states or localities, but only to the federal government. In Chicago this notion was challenged by Otis McDonald who sued the city over its handgun ban.

A Democrat who has lived on the city’s South Side since 1972, McDonald came face to face with urban decay and skyrocketing violence. Once, after reporting gunfire to police, he was confronted by a man who threatened to kill him for having called the cops. “I just got the feeling that I’m on my own,” he said. “The fact is that so many people my age have worked hard all their life, getting a nice place for themselves to live in … and having one [handgun] would make us feel a lot more comfortable.”

Joining McDonald as plaintiffs in the case were Colleen and David Lawson who were victims of an attempted home invasion, and former police office Adam Orlov who questions the utility of gun control laws. “The law only prohibits the actions of those who are law-abiding,” he says. “The more law-abiding the more likely you are to be vulnerable to the activities of criminals,” he concludes.

In finding for the plaintiffs in the case, the Supreme Court concluded that the Second Amendment does indeed apply to the states. “We have previously held that most of the provisions of the Bill of Rights apply with full force to both the Federal Government and the States,” wrote Justice Alito. “Applying the standard that is well established in our case law, we hold that the Second Amendment right is fully applicable to the States.”

Right, But Still Wrong

Gun rights advocates have celebrated this ruling and the National Rifle Association immediately began preparing new lawsuits based on the Court’s decision. “The NRA is preparing [our] next round of legal challenges,” NRA lobbyist Chris Cox told Ben Smith at Politico. “What [the Supreme Court] said is what we’ve said all along. Every law-abiding American has a right to a gun regardless of where they live.”

This sentiment was echoed by Randy Barnett, a professor of constitutional law at Georgetown University in a column published by The Wall Street Journal. The ruling, Barnett wrote, is “a great victory for enforcing the original meaning of the Constitution.”

But opponents of gun rights are welcoming the decision as well. “I actually like the Heller decision and the McDonald decision because they put the Second Amendment in the context of all the other amendments,” said Jackie Hilly, the executive director of the group New Yorkers Against Gun Violence. “People from the gun lobby like to promote the idea that you have an absolute or god-given right to possess a gun. That’s clearly not true; your right can be restricted.”

Also welcoming the decision from the gun-control side was Paul Helmke, president of the Brady Center and Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. “We are reassured that the Court has rejected, once again, the gun lobby argument that its ‘any gun, for anybody, anywhere’ agenda is protected by the Constitution,” he said in a statement. “The Court again recognized that the Second Amendment allows for reasonable restrictions on firearms, including who can have them and under what conditions, where they can be taken, and what types of firearms are available.”

The acceptance of the decision by gun control advocates suggests that the McDonald decision has substantial flaws, if viewed from a constitutionalist viewpoint. The most obvious flaw is Alito’s contention that the Second Amendment does not preclude “reasonable” restrictions.

“It is important to keep in mind that Heller, while striking down a law that prohibited the possession of handguns in the home, recognized that the right to keep and bear arms is not ‘a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose,'” Alito wrote for the majority. “We made it clear in Heller,” he emphasized, “that our holding did not cast doubt on such longstanding regulatory measures as ‘prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill,’ ‘laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sales of arms.’ We repeat those assurances here.”

He concludes this sop to the gun controllers by promising: “incorporation does not imperil every law regulating firearms.”

The Question of Incorporation

Despite his acquiescence to various forms of gun regulation, Alito and the majority on the court concluded: “We therefore hold that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment incorporates the Second Amendment right recognized in Heller.”

The question of incorporation of rights comes down as a legacy of the question of slavery and the outcome of the Civil War. The Taney Court, in its infamous decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, held that people of African descent and imported into the United States as slaves were not citizens under the Constitution and therefore did not have rights, were not subject to due process, and did not enjoy the privileges and immunities of the people of the several states.

The Fourteenth Amendment was adopted in the wake of the Civil War in large measure to rectify the injustice of Dred Scott. But, just a few years after the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the question of its meaning and applicability came to the fore in the Slaughter-House Cases before the Supreme Court in 1873. Among other things, regarding the Amendment, the Court found in Slaughter-House “that persons may be citizens of the United States without regard to their citizenship of a particular State, and it overturns the Dred Scott decision by making all persons born within the United States and subject to its jurisdiction citizens of the United States.”

In its text relevant to discussions of its incorporation of the Bill of Rights, the Amendment reads: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

But the court in Slaughter-House defined the application of the “privileges and immunities” clause very narrowly. In the court’s decision in that case, Justice Miller found that the clause protects only rights “which owe their existence to the Federal government, its National character, its Constitution, or its laws.”

Author Laurence Vance, in his valuable study of the Fourteenth Amendment, points out that the reference to “privileges and immunities” can be traced to the Articles of Confederation where they were defined as “free ingress and regress” to and from the states, and “privileges of trade and commerce,” with respect to “duties, impositions, and restrictions” on property. In its restrictive understanding of “privileges and immunities,” Vance points out, the Court in Slaughter-House, found that “there can be but little question that the purpose of both these provisions [in the Articles and the Constitution] is the same, and that the privileges and immunities intended are the same in each.”

In other words, as a result of Slaughter-House and later decisions, the Bill of Rights, dealing with those natural rights preexisting the Constitution, were not subject to incorporation under the Privileges and Immunities clause.

In his concurring opinion in McDonald, Justice Clarence Thomas disagrees. By vastly restricting the understanding of the Privileges and Immunities clause, he opines, the Court in its earlier rulings was guilty of legal sleight of hand. In its rulings, according to Thomas, the court is saying that “the reason the Framers codified the right to bear arms in the Second Amendment — its nature as an inalienable right that preexisted the Constitution’s adoption — was the very reason citizens could not enforce it against the States through the Fourteenth.” This “circular reasoning” he says, “has been the Court’s last word on the Privileges or Immunities Clause,” henceforth forcing litigants to search for “an alternative fount of such rights.” This they found in the Due Process clause.

As Justice Thomas notes, in time “the Court came to conclude that certain Bill of Rights guarantees were sufficiently fundamental to fall within [the Fourteenth Amendment’s] §1’s guarantee of ‘due process.'” In McDonald, ultimately, the Court found that the Second Amendment could be so incorporated. This conclusion by the Court led the media to cover the decision with headlines referring to the Court having now “extended” the right of firearms ownership beyond its previously restricted sphere.

Byzantine Baloney

Could it really be that it takes this amount of sophistry from the nation’s highest court to determine whether or not a fundamental, preexisting natural right (for such it must be if not included, according to Slaughter-House, among privileges and immunities) can be exercised by citizens?

In fact, present day scholars and authors, as well as past Justices of the Supreme Court, have found the incorporation doctrine questionable. In the wake of the Kelo decision on eminent domain, Congressman Ron Paul advised that constitutionalists who “hope to maintain credibility … must reject the phony incorporation doctrine in all cases.”

Speaking with The New American, legal scholar and constitutional law expert Edwin Viera said the incorporation doctrine is “mumbo jumbo.” Explaining, he says, “It has absolutely no constitutional basis. It gets you vaguely to the right result, but constitutionally it’s nonsense.”

As far as the Supreme Court goes, Justice Felix Frankfurter no less, in Adamson v. California (1947), argued: “The notion that the Fourteenth Amendment was a covert way of imposing upon the States all the rules which it seemed important to Eighteenth Century Statesmen to write into the Federal Amendments, was rejected by judges who were themselves witnesses of the process by which the Fourteenth Amendment became par of the Constitution.”

Indeed, the Second Amendment does not need the 14th Amendment to be applied to the States. “Of course the Second Amendment applied to the states,” said Viera. Of course the states couldn’t disarm people because these things were the militia of the several states composed of the people of the several states. This is obvious.”

Elaborating, Viera continued: “The second amendment applies to the states because the people that are referred to in that amendment, who are those people? They are the people living in the states and they are the members of the states’ militias, the militias of the several states.”

As to whether the Second Amendment, and, in fact, the entire Bill of Rights, applies to the people, regardless of what the Supreme Court may say, the Constitution itself is quite clear on the matter. In his commentary on the Constitution, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story pointed out that in the Preamble, “the language is ‘We the people of the United States.’ not We, the states, ‘do ordain and establish…'” It is, he says, “an ordinance … [that] binds as a fundamental law … between each and all the citizens of the United States, as distinct parties.” As such, while the Constitution clearly establishes the Federal government, it recognizes in so doing the rights both of the states and of the people. In so doing it recognizes that the natural rights it protects are inherent in the people themselves and are protected from government intrusion and restriction at all levels.

This would seem to have been Madison’s view in particular with regard to the Second Amendment. In its very first clause, as proposed by the “Father of the Constitution,” the Amendment said simply, “The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

McDonald, it seems, gets the decision mostly right, but it is not as strong a finding in favor of the Second Amendment and the natural law as it might have been.

Photo of Otis McDonald in front of the Supreme Court: AP Images