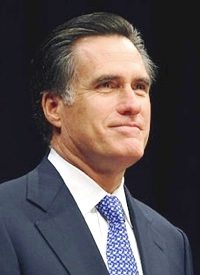

Who will be in charge of the executive branch of government if Mitt Romney is our next President? Who will be making the decisions coming out of the White House, decisions affecting matters as crucial as the question of war or peace? When Romney ran for the 2008 nomination, he was asked a rather basic question by Chris Matthews of MSNBC during one of the many televised debates.

“Governor Romney, if you were President of the United States, would you need to go to Congress to get authorization to take military action against Iran's nuclear facilities?”

“You sit down with your attorneys and [they] tell you what you have to do,” Romney said. “But obviously, the President of the United States has to do what's in the best interest of the United States to protect us against a potential threat. The President did that when he was planning on moving into Iraq and received the authorization of Congress."

“Did he need it?” Matthews interjected.

“You know, we're going to let the lawyers sort out what he needed to do and what he didn't need to do,” Romney replied. “But certainly what you want to do is to have the agreement of all the people in leadership of our government, as well as our friends around the world when those circumstances are available.”

You sit down with your attorneys and tell you what you have to do. The missing pronoun in that sentence, as transcribed from the video below, is obviously, “they,” referring back to the attorneys. Romney would let “the attorneys” tell him what he would “have to do.” He would “let the lawyers sort out” what the President “needed to do and what he didn't need to do.” He would want “the agreement of all the people in leadership in government, as well as our friends around the world” — but not necessarily the agreement of the Congress.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VdFk8nLxQjc

There are some lawyers, and others, who like to “sort out” the congressional power to declare war to mean the President may initiate a military campaign without congressional approval. That Presidents have done so is undeniable. President Truman's “police action” in Korea and President Obama's “humanitarian intervention” in Libya come readily to mind. The question is whether those actions were consistent with the oath every President has taken to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

John Yoo, professor of law at the University of California and a former Justice Department official, argues that it is. In an article that appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Yoo wrote: “When the Constitution was written, a declaration of war served diplomatic notice about a change in legal relations. It had little to do with launching hostilities.” But if that narrow view of the congressional power is what was meant when the Constitution was written, a great many of the Framers were unaware of it. Even Alexander Hamilton, the great champion of “energy in the executive,” argued that the Constitution gives primacy of power to the legislative branch on the issue of war. In The Federalist, no. 69, Hamilton wrote the following:

The President is to be commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the United States. In this respect his authority would be nominally the same with that of the king of Great Britain, but in substance much inferior to it. It would amount to nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces, as first General and admiral of the Confederacy; while that of the British king extends to the declaring of war and to the raising and regulating of fleets and armies — all which, by the Constitution under consideration, would appertain to the legislature.

James Madison, hailed by his colleagues as the “Father of the Constitution,” later wrote to fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson: “The constitution supposes, what the History of all Governments demonstrates, that the Executive is the branch of power most interested in war, and most prone to it. It has accordingly with studied care vested the question of war in the Legislature.” Our first President, who was also president of the Constitutional Convention, agreed. "The Constitution vests the power of declaring war with Congress," Washington declared, "therefore no offensive expedition of importance can be undertaken until after they have deliberated upon the subject, and authorized such a measure."

“To declare War” is a “Power” the Constitution delegates to the Congress. (Article I, Section 8). If that meant only to announce to the world the beginning of hostilities, it would hardly qualify as a “Power” of the legislative branch. It would seem more a job for the State Department or even a White House Press Secretary.

But after leaving it to “the lawyers” to decide whether the President may start a war, Romney would let another group of unelected officials decide when to end it. Asked in a debate in New Hampshire last June if the time had come time to bring the troops home from the 10-year-old war in Afghanistan, Romney deferred to the generals:

It's time for us to bring our troops home as soon as we possibly can, consistent with the word that comes from our generals that we can hand the country over to the Taliban military in [a] way that they're able to defend themselves — it should be the Afghan military — to defend themselves from the Taliban. That's an important distinction.

Naturally, any President would want to consult with the generals before making a military decision. But Romney appears willing to let the generals make the decision. “I want those troops to come home,” he added, “based not upon politics, not based upon economics, but based upon conditions on the ground, determined by the generals.” Another presidential candidate, Congressman Ron Paul (R-Texas) was asked if he agreed.

“Not quite,” Paul said in a rare understatement. If he were President, he said, “I wouldn't wait for my generals. I'm the commander in chief, I make the decisions, I tell the generals what to do, and I'd bring [the troops] home as quickly as possible.”

Romney likes to boast of his executive experience as a businessman as evidence of his ability to lead the nation. But his presidential campaign raises questions about a number of factors, including his decision-making ability. What he has revealed thus far about how he would govern as President might even raise some doubt as to whether he was even the one making the decisions — for good or ill — during his lucrative career at Bain Capital. He has, throughout his political career, been vague about a number of things, including where the power of nation's chief executive begins and ends. Truman made famous a sign on his desk that said, “The buck stops here.”

Romney might want a sign that says, “Ask my lawyers.”