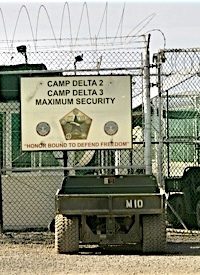

The Associated Press noted in an exclusive report on August 6 that the CIA secretly moved four suspected high-level terrorist prisoners to the Guant?namo Bay Detention Camp on September 24, 2003, and then on March 27, 2004 — in anticipation of a Supreme Court ruling giving the detainees access to U.S. courts — moved the prisoners out of U.S. jurisdiction to the CIA’s "black sites," a name given to the spy agency’s secret overseas detention facilities.

President Obama issued an executive order closing the CIA’s black sites on January 23, 2009.

Among the suspected al-Qaeda operatives aboard the September 2003 flight were Ramzi Binalshibh and Mustafa al-Hawsawi, who helped plan the 9/11 attacks; Abd al-Nashiri, the mastermind of the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole; and Abu Zubaydah, identified as an al-Qaeda travel facilitator.

The Supreme Court ruled on June 28, 2004, that detainees should have access to U.S. courts. If the prisoners had remained in Guantnamo three months longer, the ruling would have had direct impact on them.

The AP report quoted Jonathan Hafetz, a Seton Hall University law professor who has represented several detainees, who stated: "This was all just a shell game to hide detainees from the courts."

AP’s researchers pieced together information about the passengers aboard the flights to and from Guantnamo by using flight records and interviews with current and former U.S. officials and others familiar with the CIA’s detention program. All of those interviewed spoke on condition of anonymity.

Top officials at the White House, Justice Department, Pentagon, and CIA were consulted about the prisoner transfer, which was so secretive that even many people close to the CIA detention program were kept in the dark. CIA spokesman George Little said: "The so-called black sites and enhanced interrogation methods, which were administered on the basis of guidance from the Department of Justice, are a thing of the past."

In a review of Judge Andrew Napolitano’s book, Lies the Government Told You, at this site on March 30, writer Thomas Eddlem noted that Napolitano devoted much of his book to exposing attacks on American liberties justified by the so-called “war on terror” and that the Justice Department under both the Bush and Obama administrations engaged in a deliberate and open attack not only on the rights of foreign detainees, but on Americans as well. Among those compromised rights are the right to afair trial, to be safe from torture, and to be free from unconstitutional surveillance. Eddlem wrote:

Napolitano admits that “the recent decision to try some of the Guantanamo detainees in federal District Court and some in military courts in Cuba is without a legal or constitutional bright line.” Napolitano concludes that “All those detained since 9/11 should be tried in federal [civilian criminal] courts because without a declaration of war, the Constitution demands no less.” Napolitano notes that “the rules of war apply only to those involved in a lawfullydeclaredwar, and not to something that the government merelycallsa war.” He also claims that “Among those powers is the ability to use military tribunals to try those who have caused us harm by violating the rules of war.”

But what precisely is a “military tribunal”? Napolitano doesn’t define it. The Constitution and its amendments make no mention of sucha body, though they do mention a separate military justice system currently used for U.S. servicemen — which neither the Bush nor Obama want to use for detainees. Moreover, the Bill of Rights explicitly prohibits the application of military commissions as they have been recently constructed by Congress and the presidency.

The Sixth Amendment bans courts which don’t have “an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed,” and requires that the “district shall have been previously ascertained by law.” But in the case of military commissions, the district of the military commissions has been "ascertained" after the crime. It’s now a bipartisan policy to create courts out of thin air to convict terrorist suspects, which leads to the obvious and justifiable charge that these would be kangaroo courts. Moreover, the Bush-Cheney administration had not limited military commissions to foreigners.

Napolitano reveals that Bush and Cheney tried to hold American citizens Yaser Hamdi and Jose Padilla without charges (and in fact did so for years) and then to charge them under military commissions after losing habeas corpus appeals at the U.S. Supreme Court.?

There are many Americans who believe that the threat of terrorism is so grave that bending the Bill of Rights a bit in order to find, apprehend, and punish terrorist is acceptable. Such thinking is made more acceptable by the fact that most terrorists are foreigners who do not share in our Western culture. Such thinking was also responsible for the detainment of Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. However, the value of precedent in applying the law is not to be underestimated: If the Bill of Rights is suspended for those deemed as “foreign” today, then those rights are not longer “inalienable,” but subjective, and may eventually be abridged for Americans, as well.

In our article, “U.S. Judge Frees Guantanamo Detainee,” posted on March 24, we wrote that the acceptability of using such no-holds-barred interrogation techniques is often seen through the same lenses used to categorize the American public’s views on crime in general, with emphasis on civil rights seen as a natural attribute of social “liberals,” while law-and-order “conservatives” are expected to embrace a tough-on-criminals stance. ??In that discussion we warned against two contrasting positions, the first generally favored by those of the “liberal” persuasion, that reasonable efforts to control our borders and enforce our immigration laws is “xenophobia” and that such discrimination against foreigners is unacceptable. ?The opposing, supposedly “conservative” position, however, is potentially even more dangerous to our liberties. It is that 9/11 inaugurated a “war on terror” that justifies the suspension of the Bill of Rights whenever and wherever “national security” dictates.

There is a third possible position, however, favored by those who reject the traditional labels in favor of a more meaningful one — “constitutionalist.” These independent thinkers will tirelessly defend all of the Constitution, which includes a mandate for our federal government to protect the states against invasion, but especially articles of the Bill of Rights that protect individual freedom against governmental tyranny.

No sane person wants to let a real terrorist get away on a technicality, free to attack our land again. But the same system of justice used to prosecute domestic criminals is adequate for prosecuting terrorists. It is not necessary to compromise our rights to ensure our security.