One thing that should be noted about General Norman Schwarzkopf’s role in the 1991 war with Iraq that has generally been overlooked: He was against the war, called Operation Desert Storm, before he was for it.

That seems to have been forgotten. or at least unmentioned, in the glowing tributes to Schwarzkopf, the top allied commander in that war, whose passing last week at the age of 78 was among the latest deaths of famous Americans in the year just ended. To be sure, the general got on board with the commander-in-chief once President George H. W. Bush made it clear that he would wait no longer for the forces of Saddam Hussein to “get out of Dodge” by vacating the occupied nation of Kuwait. But initially he had indicated that he would have preferred to give the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq more time to work rather than launch prematurely a military action that would “kill a whole bunch of people.”

We tend to remember Desert Storm kindly because it was wildly successful, mercifully, and resulted in a remarkably small number of U.S. and allied casualties. But it did kill a “whole bunch of people” in Iraq and Kuwait and, as is so often the case with wars, it planted the seeds for the much longer and more costly war that began a dozen years later under the second President Bush. For as surely as the terms of peace imposed at the end of World War I set the stage for World War II, so did the famous victory of Bush War I under George H. W. Bush lead not only to the presidency of one William Jefferson Clinton, but also to Bush War II under George W. Bush, who was determined to drive Saddam Hussein not out of Kuwait —that had been accomplished (“Thanks, Dad”) — but out of Iraq itself. The younger Bush changed American policy in the Middle East and, indeed, the rest of the world with the “Bush doctrine,” leading to what he would later call the “catastrophic success” in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

When Iraq invaded and overran neighboring Kuwait on August 2, 1990, the world waited to what the reaction of the West would be. The response was by no means foreordained. The United States had no treaty obligation or even implicit understanding requiring an armed defense of Kuwait. Iraq during the 1980s was a de facto ally of the United States in its war with Iran, a nation that had provoked the wrath of Americans by seizing the U.S. embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979 and holding 53 Americans hostage for 444 days, finally releasing them when Ronald Reagan replaced Jimmy Carter in the White House on January 20, 1981.

But the elder President Bush returned from a meeting with Great Britain’s “Iron Lady,” Margaret Thatcher (“Remember, George, this is no time to go wobbly.”) determined to reverse the invasion, and pledging: “This naked aggression will not stand.” Both by word and deed, Bush showed a determination to use America’s network of alliances and unchallenged military superiority to create a “new world order” to succeed the balance of power that had prevailed between the United States and the former Soviet Union in the post-World War II era.

While the United States and its coalition partners built up a force of 500,000 troops in Saudi Arabia, a series of international economic sanctions was imposed against Iraq in an effort to convince the Baghdad regime that remaining in Kuwait was not worth the economic hardships suffered, along with the near certainty of eventual military consequences if Saddam did not give in. As the face-off in the desert continued through the fall and early winter, the political debate was focused on whether the sanctions should be given more time to work or whether it was time to turn to military force as the “last resort.”

Though administration officials and spokesmen initially claimed that no authorization from Congress would be needed for the president to launch a counter-invasion, the issue eventually came to the Congress in the form of a request for the Authorization for the Use of Military Force. The debate came to a head in early January, when Rep. Barney Frank memorably challenged the assertion that the members of Congress needed to support “American foreign policy.”

“What are we,” asked the Massachusetts Democrat, “the Canadian consulate?”

Though the debate did not break entirely along party lines, Republicans generally backed President Bush’s determination to launch the military option, while most Democrats argued for staying with the options a while longer. In the Senate, Sam Nunn, a Democrat from Georgia, made an eloquent case for staying with the Desert Shield defensive posture in Saudi Arabia while relying on the sanctions, rather than starting a war at that time. Nunn’s opposition to the war resolution was significant, given his history and reputation of stalwart support of a strong military and a robust assertion of American prerogatives and defense of American interests around the world. No one would accuse Sam Nunn of being an apologist for Saddam’s aggression or being afraid of using our nation’s military power.

Yet Nunn professed to be puzzled by the alleged urgency ascribed to the passage of the resolution. Essentially, his question was, what’s the rush? Did anyone think, he asked, when the sanctions were imposed in August that they would have achieved the withdrawal of Iraq from Kuwait in just five months? Obviously Iraq was weakening, militarily as well as economically, from its inability to purchase the parts and equipment needed to sustain its war machine. Why not let the sanctions continue that weakening effect before making a decision for war? The administration, on the other hand, expressed concern that neither the sanctions nor the coalition against Saddam would hold up indefinitely and the time had come for the West to either fish or cut bait.

In his speech on the Senate floor, Nunn invoked the name, words, and reputation of General Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East. Though the four-star general had not yet reached the legendary status that the whirlwind war in the desert would bestow on him, he was, as his high rank and command indicated, a well-respected military figure in Washington. And Nunn had at his fingertips quotations from Schwarzkopf stating the firm opinion that there was no reason to rush into war with Iraq.

“I can think of no better person to quote than General Norman Schwarzkopf, Commander of U.S. forces in the Gulf, who will bear the heavy responsibility of leading American forces into combat, if war should occur,” Nunn said as he moved to the conclusion of his speech. He continued:

On the question of patience, General Schwarzkopf said in mid-November in an interview, quoting him:

“If the alternative to dying is sitting out in the sun for another summer, then that’s not a bad alternative.” On the question of cost of waiting for sanctions to work, General Schwarzkopf also said in an interview in November, quoting him:

“I really don’t think there’s ever going to come a time when time is on the side of Iraq, as long as the sanctions are in effect, and so long as the United Nations coalition is in effect.”

On the question of effect of sanctions, General Schwarzkopf said in October — and this is immediately prior to a major switch in the Administration’s policy — immediately prior to it — quoting General Schwarzkopf:

“Right now, we have people saying, ‘OK, enough of this business; let’s get on with it.’ Golly, the sanctions have only been in effect about a couple of months …. And now we are starting to see evidence that the sanctions are pinching. So why should we say ‘OK, we gave them two months, they didn’t work. Let’s get on with it and kill a whole bunch of people.’ That’s crazy. That’s crazy.” End quote, from the Commander in the field.

Sen. Nunn was also unequivocal in asserting the right and power of Congress, rather than the president, to decide whether the United States would go to war. “There are many gray areas where the Congress, by necessity, has permitted and even encouraged and supported military action by the Commander-in-Chief without specific authorization and without a declaration of war,” Nunn said. “I do not deem every military action taken as war. I think there is always room for debate on definitions. But a war against Iraq to liberate Kuwait initiated by the United States and involving over 400,000 American forces is not a gray area.”

Congress did not, of course, declare war. Nor did it decide, by passing the resolution sought by the White House, that the nation would go to war. The resolution authorized the president to undertake military action to drive Iraq from Kuwait if he found it necessary, but left the decision up to him. It was another example of congressional buck-passing. But Bush seemed to resent having to ask the Congress for even that much. When he campaigning for reelection the following year he made the following breathtaking assertion: “I didn’t have to get permission from some old goat in Congress to kick Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait.”

Such a statement cannot be explained in terms of ignorance of or even indifference to the Constitution that Bush had sworn to uphold as president. It was an expression of outright contempt for the prerogatives of Congress and limitation on the power of the executive branch contained in that same Constitution.

As it turned out, the national euphoria over the air war over Iraq and the 100-hour ground war in Kuwait was as short-lived as the war itself. Bush’s approval rating at war’s end reached 91 percent and most Democratic presidential hopefuls were reluctant to enter the fray against a president with that kind of popularity.

So while New York Gov. Mario Cuomo continued a straddle on the sidelines and little-known Sen. Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts mounted a presidential campaign that few were taking seriously, the governor of Arkansas, one Bill Clinton, was quietly plotting his own campaign, one that would formally begin later in the year, when the aura surrounding George the Conqueror was already fading. The 1992 election would not be about who stood up to Saddam Hussein, but about who was minding the nation’s economy that was, as Bush would described it in early 1992, “in a freefall.”

While Cuomo and others fiddled, Clinton knocked off Tsongas and captured the nomination. Then he beat Bush, whose triumph in the Gulf War was hardly remembered when the general election was held nearly two years later. The was for the first President Bush what his son would later call the next war with Iraq: a “catastrophic success.”

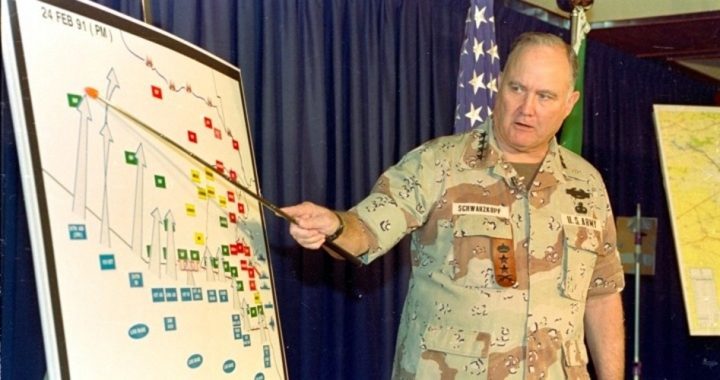

Photo of Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf: AP Images