The easiest way to secure such “willing participation,” of course, is to make it pay — something the Central Intelligence Agency, with the unwilling participation of American taxpayers, did to great effect in its program of prisoner renditions. Detainees picked up anywhere in the world were, for the modest price of $4,900 an hour, flown to countries ruled by brutal regimes to be tortured until they confessed to crimes or provided evidence against others. Those who have tried to challenge their treatment in court have been denied justice because the government always invokes “state secrets.” The Washington Post estimates that the CIA “paid tens of millions of dollars to use private planes in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks to transport detainees and its own personnel.”

Now, however, an obscure billing dispute between aircraft companies has revealed the details, including the $4,900-an-hour price tag, of the rendition flights; and the picture it paints is not at all flattering to anyone involved. The dispute, between aircraft broker Sportsflight and aircraft operator Richmor, ended up in an upstate New York court, where the documents submitted as evidence were discovered by the legal charity Reprieve, which then passed them on to several news outlets.

Sportsflight, it seems, was hired by CIA contractor DynCorp “to secure a plane with 10 seats and a range of nine hours for chartered flights,” according to the Post. Sportsflight, in turn, hired Richmor with the understanding that Richmor would have a crew ready to fly on 12 hours’ notice.

And fly it did. “Invoices submitted to the court as evidence tally with flights suspected of ferrying around individuals who were captured and delivered into the CIA’s network of secret jails around the world,” writes the Guardian. Those invoices, said Reprieve’s Clare Algar in an accompanying commentary, “lay out the financial record of the operations, including catering bills, crew costs, flight planning charges, overflight permissions and other assorted mechanisms that made the program as a whole possible.”

Algar notes that the plane “flew at least 55 missions for the US government, often to Guantánamo Bay, as well as to numerous destinations worldwide,” including “Kabul, where the CIA ran the notorious ‘Salt Pit’ prison; Bangkok, where Abu Zubaydah was first taken and used as a guinea pig for ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’; Rabat, where prisoners were kept incommunicado and tortured by Moroccan agents who passed information to the U.S. and Britain; and Bucharest, one of the European secret jail sites.”

Some of the itineraries can be tied to specific known incidents of rendition. “One Gulfstream jet,” the Guardian explains, “has been identified as the aircraft that rendered an Egyptian cleric known as Abu Omar after CIA agents kidnapped him in broad daylight in Milan in February 2003 and took him to Cairo, where he says he was tortured.” Another was used to render Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged 9/11 mastermind.

As the details of the rendition program trickled out, Richmor found itself in a dangerous position. The plane with tail number N85VM was identified after the Abu Omar rendition, after which, says the Post:

Richmor changed the tail number of the Gulfstream and complained in a letter to Sportsflight that it became the subject of “negative publicity, hate mail and the loss of a management customer as a consequence of the association of the N85VM with rendition flights.” The letter also stated that Richmor crews were not comfortable leaving the country and that the owners “are afraid to fly in their own aircraft.”

It is difficult to feel much sympathy for a company that was knowingly violating U.S. and international law, not to mention plain old human decency. None of those involved in these flights can plead ignorance of what he was doing. As the Guardian points out, on rendition flights prisoners “were usually sedated through anal suppositories before being dressed in nappies and orange boiler suits, then hooded and muffled and trussed up in the back of the aircraft.” Unless the prisoners on the Richmor flights were treated quite differently, the pilots and other crew had to know they were involved in something seedy. Moreover, Richmor’s attorney told the Post that “the company president became aware of what the planes were being used for shortly after the flights began.”

Either because he is gullible or because he was trying to put a patriotic sheen on his avarice, Richmor president Mahlon Richards claimed to have continued with the flights because he believed the government’s line that it was just doing what was necessary to protect the country from terrorists. Writes the Guardian:

[Richards] told the court that the aircraft carried “government personnel and their invitees.” “Invitees?” queried the judge, Paul Czajka. “Invitees,” confirmed Richards. They were being flown across the world because the U.S. government believed them to be “bad guys,” he said. Richmor performed well, Richards added. “We were complimented all the time.” “By the invitees?” asked the judge. “Not the invitees, the government.”

“No doubt,” Floyd remarks acidly. “All those who take part in the vast machinery of torment and state terror have been praised, rewarded and protected by the government, in both the Bush and Obama administrations.”

Other documents revealed in the court case include “logs of air-to-ground phone calls made from the plane,” according to the Post. “These logs show multiple calls to CIA headquarters; to the cell- and home phones of a senior CIA official involved in the rendition program; and to a government contractor, Falls Church-based DynCorp, that worked for the CIA.” There is simply no denying that Richmor was doing the CIA’s bidding.

Oddly enough, the government, which has tried desperately to keep the details of the rendition program secret, seemed not to have the slightest interest in the case. Writes the Post:

“I kept waiting for [the government] to contact me. I kept thinking, ‘Isn’t someone going to come up here and talk to me?’ ” said William F. Ryan, the attorney for Richmor …. “No one ever did.”

[Sportsflight owner Donald] Moss’s attorney, Jeffrey Heller, also said he was never contacted by any government official.

But if, as the government would have it, the rendition program is so essential to U.S. security that no one must be permitted to challenge it in court lest its details become known, why did it allow the specifics of the Richmor flights to enter into the public record? One possibility is that the CIA isn’t as omniscient as it would like us to think it is; perhaps the agency simply overlooked the Richmor case. On the other hand, maybe, as Algar suggests, “what the CIA seeks to protect in renditions cases is not a genuine ‘state secret’ so much as its own prerogatives.”

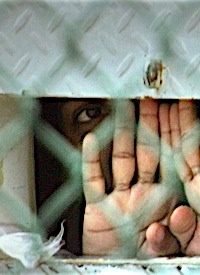

Photo of detainee peering out from his cell at Guantanamo: AP Images

Related articles:

CIA Has Become “One Hell of a Killing Machine,” Official Says