In a huge victory for religious freedom and civil liberty, the Oklahoma House of Representatives voted this week to provide an exemption to biometric collection, retention, and storage for state-issued drivers’ licenses and ID cards. SB 683 also directs that the biometric data previously collected from exempted persons be wiped from the database.

The bill, which now goes back to the State Senate, where it is expected to pass, will bring Oklahoma into compliance with the Federal Real ID law, but protect its citizens from having to obtain a biometric ID. House sponsor Jon Echols explained that while the bill does bring the state into compliance with federal law, those individuals who opt for a traditional ID would not be able to board a plane using that form of ID. But they could use an alternative form of ID, such as a passport.

The federal ID Act passed Congress in 2005, in reaction to the attacks of September 11, 2001. Those arguing for the Real ID said that the 19 hijackers used fake documents and 364 aliases. The law created minimum standards for state-issued driver’s licenses and state-issued identification cards (for those citizens who do not drive).

About half the states, including Oklahoma, passed laws refusing to implement Real ID, in effect nullifying the law. But using the fact that a person would not be able to board an airplane without the enhanced ID, or enter certain federal buildings, pressure has been brought to make states compliant with the law, anyway.

In 2007, Oklahoma passed its measure opposing the federal law, citing privacy concerns. Representative Echols said many in both political parties, and of various political philosophies opposed Real ID. His measure offers individuals a choice, if they feel uncomfortable with sharing personal information with the federal government.

“They were all against it for the same reason, everybody wants security but they were all afraid about privacy,” Echols said.

The action of the House is the result of a compromise, accomplished because the Oklahoma Legislature used its constitutional power to nullify federal law in its state, and, perhaps even more importantly, because one woman had the courage to refuse to submit to giving up her biometric data not only to the state of Oklahoma, but to the federal government, and even foreign governments.

That woman is Kaye Beach. She sparked the resistance in Oklahoma by choosing not to renew her driver’s license. She is an example of the difference that one person can make in advancing the cause of liberty. Her story should provide inspiration and hope to others who are concerned about the growing threats to individual liberty in the United States.

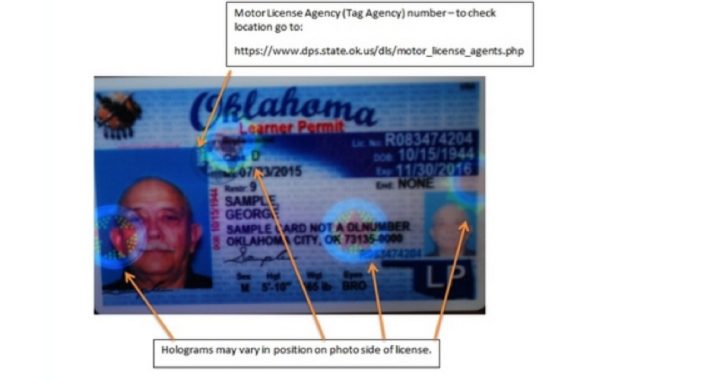

The Real ID Act was passed in 2005 purportedly to address security questions identified by the 9/11 Commission with obtaining drivers’ licenses and other forms of government-issued identification. Under the Real ID Act, the states were told to reissue more than 240 million drivers’ licenses, starting in 2010. The Department of Homeland Security issued nearly 300 pages of guidelines for state-issued drivers’ licenses and identification cards, as well as standards for license-issuing facilities. The guidelines required physical features on the licenses, including machine-readable data. Agencies that issued the IDs were required to capture digital images of driver identification documents, photograph each person applying for a license, and store the images electronically in a transferable format that can be shared with other entities.

Civil libertarians raised the concern that Real ID was yet another intrusion of the federal government into citizens’ lives, and raised the specter of a nationwide database of personal information. Of particular concern was the provision requiring that the state IDs include high-resolution photographs and fingerprints for potential biometric identification.

Beach was among those very concerned about what had happened. She began working with the Constitutional Alliance, a privacy group opposed to the government use of biometrics. Then, when her driver’s license expired, she fought back. “I realized the state was not going to protect us and so I opted against renewing my license,” Beach recalled.

Despite having met all of the other requirements for license renewal, the renewal was denied when she refused the high-resolution photos. In 2011, Beach was ticketed for driving with an expired license. A month later, she again tried to renew her license, but was again denied. Beach asked she be allowed to use a low-resolution photograph of her license, based on religious grounds. The Oklahoma Department of Public Safety (DPS) refused her request, insisting that state law did not provide alternatives or allow exemptions for the digitalized photos.

Working with the conservative Rutherford Institute, Beach’s attorneys, Eileen Echols, Jonathan Echols, and Benjamin Sisney of Echols and Associates filed a civil suit in the district court of Cleveland County against DPS for not accommodating Beach’s religious beliefs in violation of the Oklahoma Religious Freedom Act.

John Whitehead, founder of the Rutherford Institute, explained what the legal argument was. “The biometric photographs digitalize your face and then put all your information into a central computer which goes worldwide, which means it’s like a facial scan.” This means, Whitehead continued, that “wherever you go, that becomes part of your ID card.” Whitehead said that Beach compared the requirement to the mark of the beast in the Book of Revelation.

“Because she will not get this type of biometric photograph on her drivers’ license, she cannot get prescription medicines, use her debit card, rent a hotel, obtain a post office box, or drive a car. The argument here, as most people know in the Book of Revelation, is that the mark of the beast won’t let you buy, sell, or move in society,” Whitehead said.

Beach contended that the DPS was in violation of state law. In 2007, Senate Bill 464 was unanimously passed by the legislature and signed by Governor Brad Henry. The legislation said, “The state of Oklahoma shall not participate in the implementation of the Real ID Act. The Department of Public Safety is hereby directed not to implement the provisions of the Real ID Act.”

In other words, Oklahoma had practiced nullification of a federal law, which they believed went beyond the enumerated powers of the federal government.

But then, the DPS proceeded to make Oklahoma’s drivers’ licenses and IDs compliant with the standards issued under the Real ID Act, despite Oklahoma law to the contrary. DPS tried to explain away why they were not following the Oklahoma law. “Though DPS is prohibited from implementing and complying with the federal Real ID Act of 2005 … DPS is permitted to use the security and biometric features that may also be set forth in the federal act, as it is the case in issuing an Oklahoma [drivers’ license] solely under state authority.”

Beach explained her opposition to what DPS was doing. “Biometric ID is the lynchpin of the modern surveillance society. Biometric means measurement of the body.”

“In truth,” Beach said, “we are being enrolled into a global system of identification and control that links our bodies to our ability to buy, sell, and travel. And, it is being done through deception, coercion, and stealth.”

Even more ominous, in Beach’s view, was that Real ID was “to impose federal guidelines that use INTERNATIONAL standards for state drivers’ licenses and ID documents.”

“In 2011, after years of work and research, I decided there was no way that I could renew my soon to be expired drivers’ license if it meant the surrender of my biometrics. I have a child, and to just give up and leave her with the legacy of government control by cataloging and monitoring people through an international biometric ID was simply not an option for me. I asked the state for a non-biometric license to accommodate me based on my sincerely held religious beliefs and was flatly refused. This left me with little choice to forgo renewing my license.”

After this, Beach obtained the services of local attorneys (one of which is the legislator who obtained the exemption from Real ID in the House-passed bill, Jon Echols) and began to fight for her rights in the courts.

By standing up and fighting the pro-Real ID forces, Kaye Beach has won a great victory for not only her own civil liberties, but also for all Oklahomans.

This is a story which demonstrates that one person can make a positive difference in the fight for our constitutional liberties.

Steve Byas is a professor of history at Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College (soon to be Randall University) in Moore, Oklahoma.