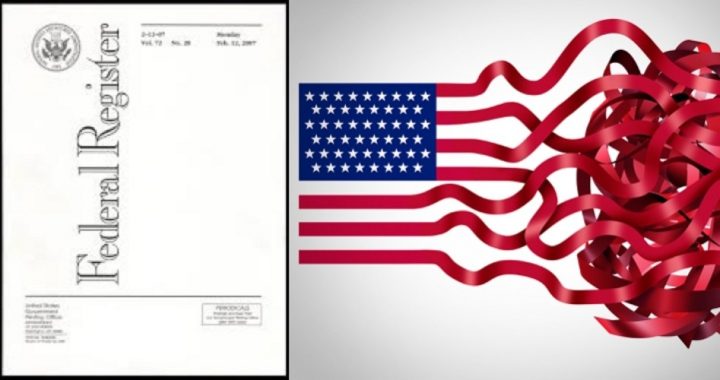

Not one to “go gentle into that good night,” Barack Obama’s administration set a record on November 17 by issuing 527 pages of new and proposed federal rules and regulations in one day. This increases the total number of pages in the daily chronicle of the central government’s edicts, the Federal Register, to a shocking 81,640 pages for 2016 alone as of Nov. 17!

Obama isn’t a newcomer to this lamentable level of legislation through regulation, however. The old high water mark for the number of pages printed in the Federal Register for one year was 81,405 set in 2010 by the Obama administration.

“No one knows what the future holds, but at a pace of well over 1,000 pages weekly, the Federal Register could easily top 90,000 pages this year,” said Clyde Wayne Crews of the Competitive Enterprise Institute. “The simple algebra says that at the current pace we’ll add 11,190 pages over the next 44 days, to end 2016 at around 92,830 pages.”

“It is remarkable enough that the all-time record has been passed before Thanksgiving,” Crews remarked.

In its coverage of the new record, the Free Beacon reports that “President Obama owns seven of the ten highest ever federal register page counts.”

Chris Rossini of the Ron Paul Liberty Report describes the United States’ descent into regulatory hell during the two terms of office “served” by Barack Obama.

“This is the anaconda that (day-by-day) squeezes the life out of the American economy. The federal government has enmeshed itself into the economic, social, and private lives of everyone,” Rossini writes.

“To call this ‘freedom’ is to completely misunderstand what freedom means. It’s authoritarianism and it grows relentlessly,” he adds.

In a chart included in the Ron Paul Liberty Report story, the pattern of rapid regulatory expansion is evident under presidents of both parties, demonstrating the duopoly’s determination to consolidate all power — legislative and executive — into the Oval Office.

In an engaging essay published by the Foundation for Economic Education (F.E.E.), Richard M. Ebeling, the BB&T Distinguished Professor of Ethics and Free Enterprise Leadership at The Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina, explains that over-regulation by the chief executive was one of the factors that brought down the Roman Empire, too.

“In A.D. 301, the famous Edict of Diocletian was passed. The Emperor fixed the prices of grain, beef, eggs, clothing, and other articles sold on the market. He also fixed the wages of those employed in the production of these goods. The penalty imposed for violation of these price and wage controls, that is, for any one caught selling any of these goods at higher than prescribed prices and wages, was death,” Ebeling explains.

In his own study of the end of ancient Rome, 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon identified an over-bloated bureaucracy as one of the contributors to the collapse of the once mighty superpower:

The number of ministers, of magistrates, of officers, and of servants, who filled the different departments of the state, was multiplied beyond the example of former times; and (if we may borrow the warm expression of a contemporary) “when the proportion of those who received exceeded the proportion of those who contributed the provinces were oppressed by the weight of tributes.” From this period to the extinction of the empire it would be easy to deduce an uninterrupted series of clamors and complaints.

According to his religion and situation, each writer chooses either Diocletian or Constantine or Valens or Theodosius, for the object of his invectives; but they unanimously agree in representing the burden of the public impositions, and particularly the land-tax and capitation, as the intolerable and increasing grievance of their own times.

Another historian, Tacitus, witnessed the decline and fall of Rome during his lifetime and in his Annals he provides his first-hand account of the unwinding of the once self-governing society of Rome.

Tacitus pointed to the increasing power of the bureaucrats as a reason republican liberty was becoming a myth in his time. He reported that the Roman Empire under Caesar Augustus employed 1,800 bureaucrats throughout the whole of the expansive empire.

While 1,800 bureaucrats may sound like a lot, that’s far fewer than those regulation-writing civil servants employed by the state of Nevada alone!

Finally, on this point Canadian classical scholar W. G. Hardy added his voice to the chorus of classicists identifying the growing Roman bureaucracy as a reasons for its demise:

Even before the plague the Roman world was rotting from within. Government paternalism, bureaucracy, inflation, an ever-increasing taste for the brutal and brutalizing spectacles of the amphitheatre and the circus were symptoms of a spiritual malaise which had begun when political freedom was tossed away in the interests of peace, security, and materialism.

In his Democracy in America, French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville warned what would happen should government become a means of regulation of the lives of Americans.

“Such a power does not destroy, but it prevents existence; it does not tyrannize, but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to be nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd,” the famous Frenchman observed.

As I wrote in a recent article on the subject:

The entirety of presidential power is defined in the Constitution. The Constitution represents the supreme law of the land, and all federal offices created therein are given specific and limited powers. If a president (or any other man holding elective office under the Constitution) ventures beyond those restrictive boundaries, he acts outside the law and those actions are absolutely without the force of law, and people are obligated to disregard them.

Perhaps this point is made most clearly in Book I, Chapter 3 of Emer de Vattel’s Law of Nations, a book that profoundly impacted every leading light of the Founding Generation from Sam Adams to James Wilson. Here is de Vattel’s statement on the subject of a ruler acting outside the limits of his constitutionally defined powers:

The constitution and laws of a state are the basis of the public tranquillity, the firmest support of political authority, and a security for the liberty of the citizens. But this constitution is a vain phantom, and the best laws are useless, if they be not religiously observed: the nation ought then to watch very attentively, in order to render them equally respected by those who govern, and by the people destined to obey. To attack the constitution of the state, and to violate its laws, is a capital crime against society; and if those guilty of it are invested with authority, they add to this crime a perfidious abuse of the power with which they are entrusted. The nation ought constantly to repress them with its utmost vigor and vigilance, as the importance of the case requires.

Finally, it is estimated that since Barack Obama took office in 2009, the regulatory burden placed on the backs of Americans has increased by about $108 billion annually.

Admittedly, the United States isn’t Rome, but we will follow her path to ruin if we continue to allow presidents — Barack Obama or his successors — to oversee the promulgation of record levels of regulations that strangle the economic life and political liberty out of the once self-governing men and women of this country.