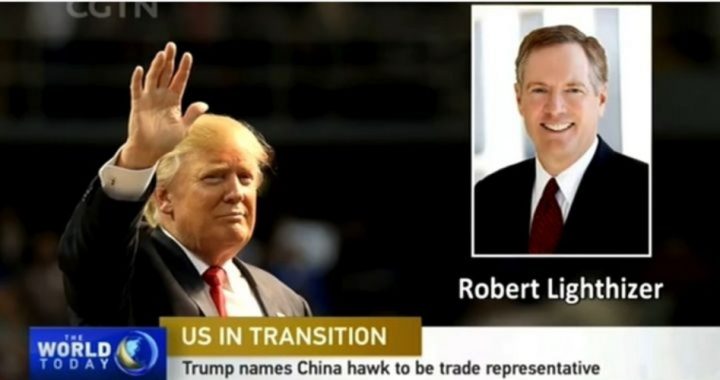

President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for the post of U.S. trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, is a free trade skeptic, who served as deputy U.S. trade representative under President Ronald Reagan.

In May of 2011, Lighthizer wrote an opinion piece in the Washington Times in response to a possible Trump campaign — in 2012, in which he asked:

Given the current financial crisis and the widespread belief that the 21st century will belong to China, is free trade really making global markets more efficient? Is it promoting our values and making America stronger? Or is it simply strengthening our adversaries and creating a world where countries who abuse the system — such as China — are on the road to economic and military dominance?

He continued,

If Mr. Trump’s campaign does nothing more than force a real debate on those questions, it will have done a service to both the Republican Party and the country.

As it turned out, Trump did not run in 2012, and eventually endorsed the Republican nominee, Mitt Romney.

Lighthizer, however, perceived then that the United States needed to rethink its trade policies, and addressed that issue with Republicans generally, and conservatives particularly.

He has long been active in the Republican Party, having served as chief of staff on the Senate Finance Committee before being tapped by President Reagan to be deputy trade representative. Later, he was national treasurer of Robert Dole’s 1996 presidential campaign. Now, he is a partner at the law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, where he specializes in international trade.

It was in the 2011 article in the Washington Times that Lighthizer publicly questioned what he called the “dogma” of free trade among Republicans, even among those viewed as leaders in conservative circles. “On a purely intellectual level,” he asked, “how does allowing China to constantly rig trade in its favor advance the core conservative goal of making markets more efficient?”

Answering his own question, he said,

Markets do not run better when manufacturing shifts to China largely because of the actions of its government. Nor do they become more efficient when Chinese companies are given special privileges in global markets, while American companies must struggle to compete with unfairly traded goods.

This issue of international trade agreements that seem to favor foreign companies and governments at the expense of American businesses and workers has been simmering at least since the presidential campaigns of Pat Buchanan and Ross Perot in 1992. While Buchanan had served loyally in three Republican presidential administrations, taking typical conservative stands throughout, when he raised the issue that international trade agreements (usually cast as “free trade”) were hollowing out American industry, costing American workers good-paying manufacturing jobs and diminishing U.S. national sovereignty, he was widely condemned as “not conservative.” Buchanan challenged President George Herbert Walker Bush, a strong free trader, for the Republican nomination. Then Texas computer tycoon Perot took up the same issue in the general election, predicting that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) would lead to a “giant sucking sound” as American industry and jobs were sent south to Mexico.

After Bush lost the general election to Democrat Bill Clinton, the Republican establishment largely made so-called free trade conservative dogma, even backing Clinton in pushing for more and more international agreements.

Lighthizer, however, contended in his 2011 Washington Times article that “free trade” was not seen as a conservative or even a Republican principle until fairly recent times. He asked, “Would anyone argue that presidents like William McKinley, William Howard Taft and Calvin Coolidge [all protectionists] were not conservatives — or that free traders like Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt were not liberals?”

Yet, Lighthizer noted when Trump considered the race in 2012 as an opponent of these so-called free trade deals, “the knives have come out for him,” with the libertarian Club for Growth dismissing him as “just another liberal.” And of course, Bush’s man Karl Rove famously stated, “He’s not one of us.”

Considering the massive domestic spending the nation experienced during the years of the George W. Bush administration, with Rove leading the way, we can certainly hope not.

“Since when does [being a protectionist] mean one is not a conservative?” Lighthizer asked in the 2011 Times article, noting that “For most of its 157-year history, the Republican Party has been the party of building domestic industry by using trade policy to promote U.S. exports and fend off unfairly traded imports.”

He then added, “American conservatives have had that view for even longer.”

“Every Republican president” generally supported tariffs for our country’s first 100 years, Lighthizer noted, while the Democrats tended to back free trade. Even more recent presidents, such as Richard Nixon in 1971, who imposed a temporary tariff on all imports from countries with unfair foreign economic policies, are cited by Lighthizer as an example of a Republican president taking an even more restrictive trade position than Trump.

“The icon of modern conservativism, Ronald Reagan, imposed quotas on imported steel, protected Harley-Davidson from Japanese competition, restrained import of semiconductors and automobiles, and took myriad similar steps to keep American industry strong,” Lighthizer added.

So this worship of Republicans (and “conservatives”) at the altar of unfettered “free trade” is a rather recent innovation. But the Republican rank-and-file — unlike its establishment — is not buying the free trade dogma. Lighthizer cited recent polling data to make his point: “Last September, an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll showed that 61 percent of Tea Party sympathizers think that free trade has hurt the United States.” Even a majority of Republicans (52 percent) consider that increased trade with China is detrimental to the United States.

Most startling, the poll noted that “only 28 percent of Republicans think free-trade agreements are good for the United States.”

Apparently, Buchanan and Perot were ahead of their time.

“The recent blind faith some Republicans have shown toward free trade actually represents more of an aberration than a hallmark of true American conservatism,” Lighthizer contended. “It’s an anomaly that may well demand re-examination in the context of critically important questions facing all conservatives on trade policy.”

Lighthizer does not directly address one of those questions that conservatives must face when it comes to trade policy, however. That is the question of national sovereignty and multilateral trade deals. While those who oppose multilateral trade agreements are often cast as “against trade,” the reality is that these agreements over the past three decades have had more to do with creating a global government (e.g., the World Trade Organization) than with “trade.” The issues of global government, “free” trade, and unrestricted immigration are inextricably tied together. As Hillary Clinton was quoted as saying, she hoped to see the elimination of trade barriers and national borders.

This can be demonstrated vividly with the European Union (EU). What began as a supposedly multilateral trade agreement among six European nations dealing simply with coal and iron has evolved over the years into its modern incarnation: a multilateral super-state, where nations’ laws and borders are overridden by the unelected global elites who rule the EU from Brussels. This is exactly why the people of the United Kingdom opted to leave the EU in last year’s historic Brexit vote.

Another example of how globalism works is in the area of trade: After an unfavorable World Trade Organization ruling against the United States for requiring the labeling of foreign agricultural products, the U.S. Congress meekly repealed the law. Now, U.S. consumers are not allowed to know the country of origin of much of the food they are eating, all in the name of “free trade.”

And what Star Wars fan can forget that the intergalactic republic was turned into an authoritarian empire following a seemingly beneficial “trade agreement”?

Perhaps the tide is now turning on this issue, with the election of Trump. As Lighthizer wrote in 2011, “Only last September [note: 2010], the House of Representatives voted to give the president the expanded authority to impose tariffs on virtually all Chinese imports in response to China’s policy of keeping its currency at an artificially low value. Republican House members voted 99 to 74 in favor of this legislation.”

While conservatives rightly believe that Congress should not be delegating more power to any president, at least the election of Trump indicates that the whole issue of trade agreements is being reconsidered.

And the appointment of Lighthizer certainly illustrates that that reassessment is picking up momentum.