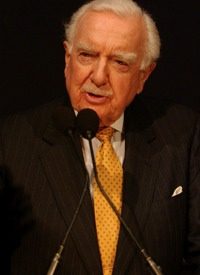

Born in 1916 and raised in St. Joseph, Missouri, Walter Leland Cronkite, Jr. rose to become the most famous news anchor in television’s history.

When a teen, his family relocated to Texas where he delivered the Houston Post at the very time his cub reporter articles would appear in its pages. He whimsically noted in his 1996 autobiography that “there were no other journalists delivering the morning paper with their own compositions inside.”

Off to the University of Texas, Cronkite studied political science and journalism. He also earned spending money as the Post’s campus reporter while putting his deep baritone voice to work broadcasting some sporting events. Offered a full-time job with the Post, he quit the university in his junior year and happily started his full-time career. In rapid succession he found employment as a radio announcer and then a writer for United Press International for whom he later toiled as a war correspondent. In one of his memorable reports during World War II, he related the experience of being in a frightening U.S. bombing raid over Germany, but he never mentioned that he was also manning a .50-caliber machine gun in case any enemy fighter plane attacked his B-17. For UPI, he covered U.S. military action in North Africa, the Normandy landing, and the 1944 Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he reported from the Nuremberg trials and then from the UPI office in Moscow.

By 1950, his abilities were recognized sufficiently for CBS to name him as the head of the news department in the network’s initial station in Washington D.C. He anchored the 1952 Democratic and Republican national conventions for CBS and became the network’s star at subsequent conventions until 1980. On April 16, 1962, he took over as the anchor for the CBS Evening News, a post he held until retiring in 1981. His nightly broadcasts attracted huge audiences and he always ended them with, “And that’s the way it is.”

Rarely expressing his own views, Cronkite would let his emotions and an occasional opinion show when he announced the news, such as when reporting John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the launch of the Apollo 11 on its way to the moon landing, the unruly demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic Party convention in Chicago, and the Watergate scandal. He stuck his neck way out in 1968 during an on-air bit of editorializing when he declared the Vietnam War to be “a no-win situation and it’s time for us to get out.” Even so, in 1973, he protested with a degree of believability that he was just a “news reporter — not a commentator or analyst.” Americans of virtually all political persuasions accepted that self-description and their attitude led to him becoming dubbed the “most trusted man” in America.

In retirement, Cronkite became a sailor and a lover of life on Martha’s Vineyard, the island off the south coast of Massachusetts frequented as a vacation hideaway by many noteworthy liberals. Once freed of any restraints (either self-imposed or mandated) about expressing his own views, he demonstrated an enduring preference for internationalism at the expense of national independence. In his autobiography, for instance, he pointed to the threat of nuclear devastation and suggested as a “mandatory alternative” a system of world order — preferably a system of "world government.” Early in 2000, he told an interviewer in England that the “American people are going to have to realize that perhaps they are going to have to yield some sovereignty to an international body to enforce world law.”

His frequently stated advocacy of world government, led in 1999 to his being presented with the Norman Cousins Global Governance Award by the World Federalist Association (WFA), perhaps the leading advocate of world government in America. WFA recognized Cronkite as an ideological ally who was willing to grant the United Nations vast new powers over all nations, most certainly including ours.

In his remarks given while joyfully accepting the WFA prize in October 1999, Cronkite insisted that the UN must be given new authority because “civilization itself is at stake.” It is imperative, he declared, that there be created a “new system governed by a democratic UN federation.” He added that “the first priority of humankind in this era” is the need to “strengthen the United Nations as a first step toward a world government.” Nations must “yield up their sovereignty, just as America’s thirteen colonies did two centuries ago,” he intoned.

During the WFA ceremony, then-First Lady Hillary Clinton lauded the former newscaster for his “continuing leadership” in the campaign that effectively calls for the cancellation of independence for all nations. The WFA to which she lent her name wants an array of additional powers for the UN including “enforcing world law through inspectors, civilian police courts and an adequate armed peace force.” This organization, saluted by Mrs. Clinton and honoring Walter Cronkite, even wants “universal membership without right of secession.”

Walter Cronkite may have been a “trusted” American when he was dispensing the news. But no American who believes in keeping America free should have trusted him once he started pushing for a UN-controlled government over mankind.