As Raven Clabough reported previously for The New American, “According to a poll conducted by Oxford University, faith and religion are … innate traits for human beings. Entitled the ‘Cognition, Religion, and Theology Project,’ the initiative took three years to complete and includes over 40 different studies in 20 countries around the world." As one of the directors of the project — Professor Roger Trigg — observed in a CNN interview:

"If you've got something so deep-rooted in human nature, thwarting it is in some sense not enabling humans to fulfill their basic interests," Trigg said.

"There is quite a drive to think that religion is private," he said, arguing that such a belief is wrong. "It isn't just a quirky interest of a few, it's basic human nature. … This shows that it's much more universal, prevalent, and deep-rooted. It's got to be reckoned with. You can't just pretend it isn't there," he said.

Apparently someone needs to tell that to Hawking, whose anti-faith argument seems to require a flight into false analogies to rally a defense. Thus Hawking declared in an interview which appeared in The Guardian: "I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark."

Hawking’s attempted argument by analogy is fatally flawed on several points. There is, in fact, a fundamental asymmetry between the self-awareness manifest in human beings and the predetermined processes of programmed devices called computers.

First, if Hawking intends to argue that man is merely a biochemically programmed computer, then his position is fundamentally untenable from the outset. Computers perform only those functions for which they are programmed, and if human beings are merely computers — no matter how sophisticated — then their every "thought" and action is preprogrammed. If human beings are simply preprogrammed computers made out of meat, then the very possibility of freedom of thought and action is illusory, and debating the meaning of life is not only irrelevant, but impossible.

Second, Hawking’s argument is flawed by the asymmetry of purpose. Computers, like all machines, do not express a sentiment regarding their final disposition; thus, one does not encounter a toaster hanging on for dear life, afraid that if it fails it will be consigned to the trash. Actually, human beings have a tendency to anthropomorphize our creations — as well as animals and objects of nature. The very act of anthropomorphizing demonstrates a fundamental asymmetry between human beings and the work of their hands: We want them to be like us, but we know that they cannot be us. No matter how sentimental people may become regarding an old car — or a rover on the surface of Mars, for that matter — the relationship is asymmetrical, because a computer, car, or rover cannot return the sentiment. A human being may loath sending a car to the scrapheap, but the car cannot express any sentiment at its own disposition and remains indifferent to either a thousand trips to the mall or running over a jogger.

Third, Hawking's attempt to attribute motive to those who disagree with his metaphysical pronouncements actually undermines his position. His misguided appeal to the virtue of courage — implicitly mocking those who disagree with him as cowards who are afraid of the dark — makes the fundamental inadequacy of his position immediately apparent. Computers are never brave or cowardly; they are neither virtuous nor evil. For example, certain microwave ovens, at the conclusion of every task, scroll the same message, “ENJOY YOUR MEAL,” because the oven’s designers thought such a message would add some sort of personal dimension. Now, the oven would be utterly indifferent to a user microwaving a frozen dinner or a pet mouse, and would display the same message on either such occasion because it is utterly incapable of the ethical discernment which flows from self-awareness. Of themselves, tools are ethically neutral; it is the human user who utilizes the tool for good or for evil.

Computers have no heaven, nor any prognostications about their ultimate fate, because they are not people. Adherents of the Turing Fallacy regularly are inclined to a confusion regarding the difference between men and machines because they fail to appreciate the fact that a machine programmed to deceive a human being into imagining it was self-aware or intelligent was programmed by a human being for the purpose of such deception. Computers deceive no one, and they have neither virtues nor vices because they cannot.

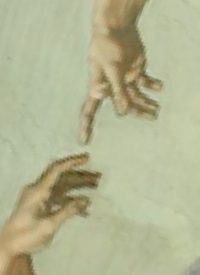

Finally, to the extent that human beings have programmed computers to mimic certain aspects of human mental activity, it is the result of purposeful, conscious, human activity. The machines were not self-programmed, nor are their programs the result of random activity or Darwinian selection. People write programs to serve a purpose. Hawking is left with a choice: If humans are meat computers, then by his analogy, someone programmed them. But since human beings are not simply computers, then their self-awareness and capacity for reflection on the mystery of their own existence means that the results of the recent Oxford study are not an expression of human cowardice, but a necessary aspect of what it means to be a human being.

Stephen Hawking’s metaphysical pronouncements are significant because they are not computer output; rather, they are the religious beliefs of a human being who has faced tremendous obstacles in life and whose views have been shaped, in part, in response to his self-aware reflections on such struggles. One may disagree with his views and still respect the man because his views are those of a moral being, and are not merely miscalculations which were spat out by a flawed computer. Looking at Dr. Stephen Hawking, one does not see a broken computer, but a brilliant man who has accomplished many worthwhile things despite grave physical disabilities. One may very well posit that his very being is further proof that he — and all human beings — are far more than our machines can ever be.