June 28, 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. While there were numerous treaties ending World War I, the Treaty of Versailles is the most famous, and in its provisions one can find many of the seeds of turmoil in post-WWI Germany that enabled Adolf Hitler and the Nazi political party to portray themselves as righteously indignant Germans eager to overturn the evils of the Treaty of Versailles. Of course, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis led Germany into yet another war, one that was even more disastrous.

Britain took no chances on letting Germany object to the Treaty of Versailles after the Armistice. The British Navy continued its blockade of German ports, making lifting the blockade conditional on approval of the treaty. The German government officials signed the treaty on June 28, and the German National Assembly voted 208 to 115 to approve the treaty on July 9. Two days later, the Superior Blockade Council lifted the blockade, effective July 12.

The British blockade was also known as the Hunger Blockade because of the food shortages it created in Germany. The German government estimated the Hunger Blockade’s death toll at 762,736 civilian deaths in Germany. This estimate included people who died of starvation as well as people who died of other diseases, with malnutrition judged by the German Board of Public Health to be a major factor. Other estimates of the civilian deaths caused by the Hunger Blockade are as low as 434,000, still a staggering death toll, especially for noncombatant civilians. The British blockade was one of the most effective military campaigns employed by Britain during The Great War, and using food as a weapon proved to be effective as a strong-arm tactic to affect political objectives within Germany after the war as well. It was also an example of British duplicity, as it was a military operation that was causing casualties when hostilities were supposed to have ceased upon the signing of the Armistice the previous November 11.

The terms of the Treaty of Versailles were so harsh that even liberal British delegate John Maynard Keynes described it as a “Carthaginian peace” and resigned his position as a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference on May 26, 1919, a little over a month before the official signing. Whether Keynes resigned as a matter of conscience or if his resignation was political posturing to let others take the brunt of the blame is up for debate.

One of the most controversial provisions of the treaty was Article 231, the War Guilt Clause, which stated:

The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.

This provision was understandably resented by the Germans, but they had no choice but to sign the treaty. This confession of guilt served as justification for reparations. Some of the reparations, such as Article 45 in which Germany ceded the Saarland and its coal mines to France, were specific, while numerous other reparation clauses were essentially blank checks, the amounts to be calculated in the future.

Another problem with the Treaty of Versailles was the creation of The League of Nations. Part 1 of the treaty was entitled “THE COVENANT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS.” Article 1 of the treaty started with:

The original Members of the League of Nations shall be those of the Signatories which are named in the Annex to this Covenant and also such of those other States named in the Annex as shall accede without reservation to this Covenant.

President Woodrow Wilson tried twice to get the U.S. Senate to ratify the treaty, but thankfully came up short both times. Some of the opposition came from the stipulation that all members “shall accede without reservation to this Covenant.” That was blatantly unconstitutional because it would have placed the League of Nations above the U.S. Constitution as the law of the land. This also would have been contrary to the advice of George Washington, who advised us to avoid entangling alliances.

Article 11 was written in somewhat cryptic terms, but most people could see that it violated the U.S. Constitution’s requirement that only Congress had the power to declare war:

Any war or threat of war, whether immediately affecting any of the Members of the League or not, is hereby declared a matter of concern to the whole League, and the League shall take any action that may be deemed wise and effectual to safeguard the peace of nations.

Article 8 had a sneaky disarmament clause:

The Members of the League recognise that the maintenance of peace requires the reduction of national armaments to the lowest point consistent with national safety and the enforcement by common action of international obligations.

Another source of opposition to the treaty came from Americans of Irish heritage. An example of their opposition was in the August 11, 1919 issue of the Washington Herald. A full-page advertisement by the Friends of Irish Freedom and Associated Societies urged Americans to contact their senators to vote no on the League of Nations. The advertisement referred to British rule in Ireland saying: “The attitude of the British Government to Ireland is that of a conqueror toward a subject race.” and added:

Yet the proposed League of Nations, through Article 10, would make the United States of America a guarantor of that empire which seeks to hold Ireland in subjection through military force and which thus offends the sense of justice of the civilized world.

Of course, there were backers of the Treaty of Versailles in America. An example of positive press toward the treaty can be found in the July 3, 1919 issue of the Bridgeport Times. The front page article, entitled “United States Bound to Come to France’s Aid In War With Hun” was written in a positive and reassuring tone toward the League of Nations and as if the treaty had already become fait accompli. Reflective of the times, it also used the pejorative term “Hun,” an ethnic slur associated with anti-German sentiment of the time that was commonly used by those in favor of going to war with Germany.

According to the National World War I Museum and Memorial, there were 29,800,700 casualties in World War I with 21,436,000 of them wounded while 8,364,700 of them died. In addition, an estimated 5,000,000 noncombatant civilians also perished. Most of the people involved in the war thought they were defending their countries, freedom, or Western Civilization. But once the war was over, might made right as globalists used the war to implement their agenda. Fortunately, the U.S. Senate wisely refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles.

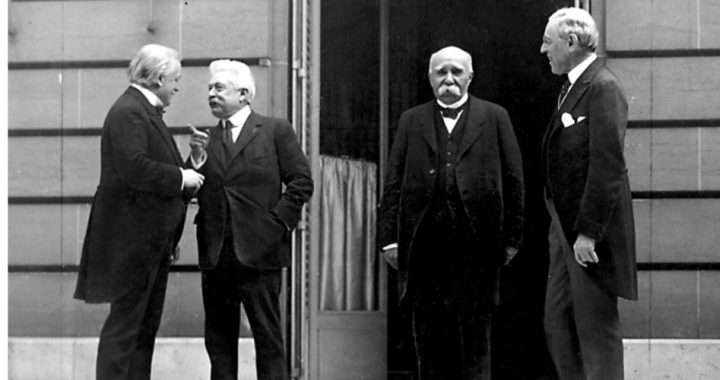

Image: Leaders of the “Big Four” at the Paris Peace Conference where the terms of the treaty were drafted (U.K. Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson)

Kurt Hyde is an election integrity expert and the first advocate for the paper trail in computerized voting equipment. He writes about election integrity and other topics.