Some at the Federal Reserve are encouraging action in order to pre-empt an economic downturn, an idea first advanced by former Fed Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan. Though the Federal Reserve’s touted role is to set policy based on the nation’s economic conditions, Greenspan believed that it was the role of the central bank to act in advance of potential risks, saying it was similar to “taking out insurance.”

In 2004, Chairman Greenspan said that central banks must manage risks, and that sometimes entails “insurance against especially adverse outcomes.” Several current members of the Federal Reserve are adhering to a similar philosophy. The New York Times reports:

On the eve of the Fed’s policy-making committee meeting on Tuesday and Wednesday, members who favor additional action argued that the likely path of the economy was itself sufficient reason for action.

Federal Reserve vice chairwoman Janet Yellen contends that the Federal Reserve should take action to offset the effects of a global financial crisis set off by a European downturn. “There are a number of significant downside risks to the economic outlook, and hence it may well be appropriate to insure against adverse shocks that could push the economy into territory where a self-reinforcing downward spiral of economic weakness would be difficult to arrest,” Ms. Yellen said in a June speech.

Laurence H. Meyer, former Federal Reserve governor who served under Greenspan, also agrees with Greenspan’s notion of “insurance” and asserts it should be a component of Federal Reserve policymaking, particularly given the current economic climate. “There are many people who look at that idea and feel that this is what was done under Greenspan, and maybe this was one of the factors that led to excessive speculation,” said Meyer. “But when the downside risks have grown as large as they have become, I think you have to consider it.”

Other members of the Federal Reserve are reluctant to make any policy changes and prefer to wait until its next meeting in September to make any decisions to determine whether the economy has lost its momentum. Additionally, the Times notes that the hesitation has something to do with “widespread concern about the waning potency of the Fed’s remaining tools, and about the cost of the most powerful measure, an expansion of its holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.” The Federal Reserve is also in an uncomfortable political position since this is an election year. Republicans are opposed to any additional action from the Fed, while Democrats encourage more action.

Leading analysts of the Federal Reserve predict that the Fed will most likely take some sort of action on Wednesday as a sign that it is attentive to and concerned about the state of the economy, while simultaneously waiting to hear more data about the economic conditions. Those analysts are predicting an extension of the Fed’s forecast that interest rates remain near zero until at least the end of 2014. Sven Jari Stehn of Goldman Sachs believes that the Fed will extend that forecast until the middle of 2015.

Some have outright rejected the notion of Greenspan that the Federal Reserve is in the business of risk management, and contend that it has in fact increased risk, particularly with policies such as keeping interest rates artificially low. Representative Ron Paul (R-Texas), an adamant opponent of the Federal Reserve, criticized this policy in October 2011:

The Federal Reserve began the second incarnation of “Operation Twist,” an attempt to drive down interest rates by purchasing long-term Treasury debt and selling short-term debt. This is just the latest instance of the central bank desperately flailing around doing something merely for the sake of doing something.

Fed officials still do not understand — or admit — that the Fed itself caused the financial crisis by driving interest rates too low and relentlessly expanding the money supply. Thus, this latest action will just exacerbate the problem.

As noted by Paul, the continued inflation of the currency supply and the Fed’s suppression of interest rates make it unprofitable to invest in things such as savings accounts, mutual funds, and Treasury bonds, all which were once considered safe havens.

While some members of the Federal Reserve believe they should take action to pre-empt economic crises, most of the Fed’s policies actually cause the economic crises. By generating more money, the Federal Reserve is increasing profits for the banks while the average consumer takes on more debt. Purchasing mortgage-backed securities keeps housing prices inflated, hurting the consumer who becomes priced out of the housing market.

The Federal Reserve has attempted to stimulate the economy through quantitative easing — the purchase of assets from banks that increase liquidity in the economy — but that simply provides an illusion of economic growth. Any faith placed in stimulus is false, according to economist Peter Schiff. “I think the only thing that is punctuating the recessions is the phony growth that we get from the stimulus. But it’s not real growth. All we do is spend more borrowed money,” said Schiff.

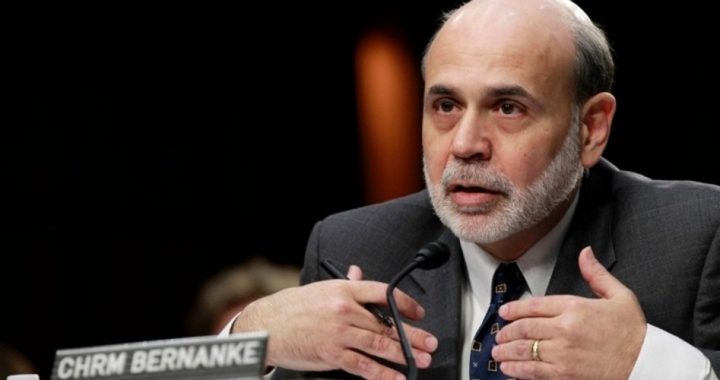

But that has not stopped Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke from telling Congress that the Fed is once again considering quantitative easing. Bernanke is convinced that the effort would drive down interest rates and improve the rate of economic growth. Bernanke points to the economy’s failure to progress after it witnessed a drop in unemployment between September and April. Bernanke has said that the Fed would continue to take action if the economy does not grow fast enough to reduce unemployment. “We are very committed to ensuring, or at least doing all we can to ensure, that we continue to make progress on unemployment,” he told Congress earlier this month.

Schiff contends, however, that repeated misguided policies are merely prolonging the inevitable. “I think we’re still in a depression. I think it’s going to be with us for years and years. It could be five or 10 years; it could be longer, depending on how long it takes us to recognize our mistakes so that we can begin to reverse them,” Schiff says.

Photo of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke: AP Images