The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) just revised its January report with new data on spending, revenues, and economic growth. The revision isn’t good:

The projected rise in [annual] deficits would be the result of rapid growth in spending for federal retirement and health care programs targeted to older people, and to rising interest payments on the government’s debt, accompanied by only moderate growth in revenue collections.

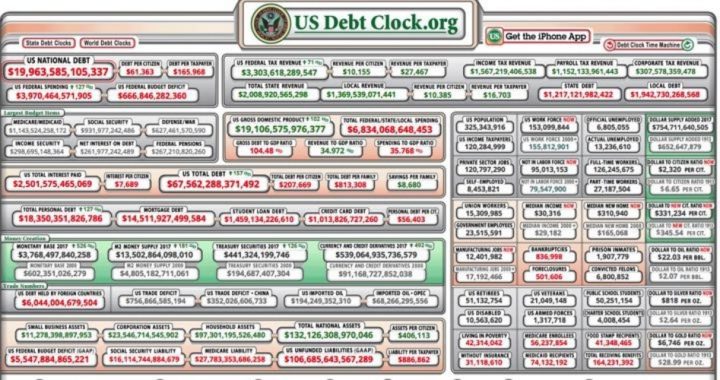

In other words, the CBO simply doesn’t believe that President Trump’s plans to reduce regulation, cut taxes, and repeal ObamaCare will amount to much. Instead the government programs on autopilot — Social Security, Medicare, and especially debt service on the country’s $20 trillion national debt — will eat up nearly 80 percent of the government’s total budget in less than 10 years. Said the CBO:

[Our] estimate of the shortfall for 2017 has increased since January — largely as a result of tax collections that have been weaker than expected — as has [our] projection of the cumulative deficit over [the next ten years].

It’s rising interest rates that are the wildcard, said the agency:

Much of the change over the 10-year period is accounted for by an increase in net interest costs, primarily a result of higher projected interest rates … and by the effects of legislation enacted after CBO prepared its January baseline.

There’s no chance that anything will reduce in the federal government’s transfer programs from the taxpayer to the retiree:

Under current law, growth in revenues would be outpaced by growth in spending for large federal benefit programs (primarily retirement and health care programs targeted for older people).

Those “older people” are counting on the government to keep its promises and are deaf to any argument that the government won’t be able to keep them. “I paid in all these years and those benefits are mine!” is the refrain. And those older people are also voters so if politicians make any move to reduce the benefits they’ve paid for all these years, the politicians will soon be out of office.

There’s also “war costs” that showed up in CBO’s revision:

The largest spending increases stem from higher projected … increase[s] in funding for overseas contingency operations (primarily for war-related activities in Afghanistan and related missions) that was provided in the final appropriations for 2017.

Just how high will those annual deficits be? As The New American reported last month, the federal government ran a deficit of $88 billion in May. On an annual basis that’s more than a trillion dollars and the CBO agrees: The annual deficits are forecast to reach $1.5 trillion annually in less than 10 years. It didn’t dare to make any forecast beyond that.

In its March revision of its January report the CBO noted that “federal debt … has ballooned over the last decade. In 2007, the year the recession began, debt held by the public represented 35 percent of GDP. Just five years later, federal debt held by the public has doubled to 70 percent and is projected to continue rising. Debt has not seen a surge this large since the increase in federal spending during World War II.”

Speaking of recessions, the economy is way past due for one. The last one, starting in 2008, prompted the government to ramp up deficits well above a trillion dollars. The average period of time between recessions is five to six years. The CBO made no mention of building a recession into its forecast, nor did it reckon the impact rising interests rates would have as investors begin to see the debt approach 90 percent of the country’s economic output. At around that point, according to Harvard economists Reinhart and Rogoff, growth tapers off as the weight of interest payments overwhelms the economy’s ability to service the national debt. Like weights added to a race horse, interest payments are a dead weight on the economy. This brings into question the CBO’s estimate that the economy will grow at two percent a year over the next 10 years. Studies by Reinhard and Rogoff show that real true economic growth could falter to below 1.4 percent a year, forcing the CBO to continue to revise its forecasts to reflect the new realities.

As Jack Salmon, an economic researcher in Washington, D.C., expressed it:

With a large and growing debt burden, the likelihood of a financial crisis in the United States is greatly increased as investors become unwilling to finance the government’s borrowing.

Policymakers must recognize this problem for what it is: a spending problem.

Image of debt clock: Screenshot at http://www.usdebtclock.org/

An Ivy League graduate and former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American magazine and blogs frequently at LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].

Related article:

Gov’t Collects Record $240 Billion in May; Still Runs $88 Billion Deficit