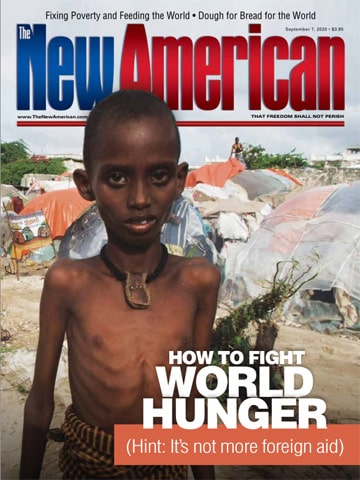

Socialist Solutions to World Poverty

Today’s [global welfare] situation is a bit like the old Soviet Workers’ joke: “We pretend to work, and you pretend to pay us!” Many poor countries today pretend to reform while rich countries pretend to help them, raising the cynicism to a pretty high level. Many low-income countries go through the motions of reform, doing little in practice and expecting even less in return.

He adds that the big public-aid agencies play the same propaganda games:The aid agencies, on their part, focus on projects at a symbolic rather than national scale, just big enough to make good headlines. In 2002, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) proudly trumpeted its West Africa Water Initiative, noting that “a reliable supply of safe water, along with adequate sanitation and hygiene are on the front line in the combat against water-related disease and death.” Fair enough, but what was USAID’s actual contribution? A pitiful $4.4 million over three years. If West Africa has a population of some 250 million people, $4.4 million over three years would be less than a penny per person per year, enough to buy a Dixie cup, but probably not enough to fill it with water.

He says that with the amount of money now spent on aid, countries such as Ethiopia would never meet the Millennium Development Goals of the UN for reducing poverty in certain timeframes, yet the public for decades has been continually fed lies to keep the status quo going: essentially, keeping the money coming in and retaining good jobs for bureaucrats. (According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 30 countries in 2016 belonging to the Development Assistance Committee (DAC)contributed a total of $142.6 billion to poor countries, while donors outside of the DAC also have contributed sizable amounts, with China alone giving $69.9 billion in 2019. This represents aid not devoted to military spending.) The fact that the UN and its affiliates lie to make themselves look good and appear to be the world’s white knights, instead of its monsters, should not be surprising to anyone who follows the UN, as the organ-ization’s corrupt core not only bubbles to the surface with regularity, but pokes out in obvious places. The New York Post reported in a 2015 article entitled “The Long Sordid Tale of Corrupt UN leadership” about the mischief that UN General Assembly presidents get into, including John Ashe of Antigua and Barbuda, who was arrested by the feds on charges of bribery-related tax evasion. The paper related,According to the rap sheet, Ashe, who was General Assembly president two years ago, allegedly received millions of dollars from a Chinese-based real-estate mogul, Ng Lang Seng.

Ng allegedly used several UN-related NGOs to transfer cash, gifts and airfare tickets to Ashe and his co-defendants, trying to enlist their help in promoting a pet project: He wanted to build a UN center in Macau.

Ironically, the bad acts brought to light by the paper were dismissed as inconsequential by the UN because the head of the General Assembly has little power. Just imagine how much trouble UN bureaucrats who have real power can get into. We know of a few examples to help spark your thoughts: • UN funds earmarked for tsunami relief in Indonesia simply disappeared. • On August 9, 2005, The Economist reported, “The UN’s biggest-ever humanitarian undertaking seems to have become its biggest-ever scandal.” At the time, Iraq had trade restrictions placed on it, and it was getting food to feed its people by selling oil via the UN. The UN’s head of the program, Benon Sevan, was taking kickbacks while he was in charge of the program, and another UN official was soliciting bribes. After the corruption came to light, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan claimed that Sevan had taken a paltry $150,000 out of $64 billion contract, reported Commentary Magazine in an article entitled “How Corrupt Is the United Nations?” However, according to an independent investigation, Sevan actually received $1.2 million, yet he was allowed to retire on a full UN pension, free of any criminal charges. Worse, “UN agencies had kept for themselves at least $50 million earmarked to buy relief for the people of Iraq.” And UN agencies charged with investigating corruption in the program spent more on renovating their New York offices with oil-for-food money than on investigating fraud. At the same time, the dictatorial head of Iraq who was supposed to be suffering from the sanctions, Saddam Hussein, was allowed to skim between $12 and $17 billion from the program to buy loyalty in his country and buy weapons. • The Commentary article also explained about “a bribery scandal centered in its procurement department, which handles the Secretariat’s buying of everything from paperclips to peacekeeper rations…. A UN staffer named Alexander Yakovlev pleaded guilty in federal court to taking hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of bribes, involving possibly hundreds of millions’ worth of tainted contracts.” • The world’s worst human-rights abusers are often members of the United Nations Human Rights Council. Members have recently included Venezuela, even as Nicolás Maduro was starving his country’s populace; Cuba, which has imprisoned, starved, and even shot political dissenters; Saudi Arabia, which commonly beheads people in public for dissent; and China, which routinely “disappears” people, tortures them, and slices them up for organ donations. • UN peacekeeping missions are rife with the rape of women and children by the troops — rapes the soldiers commit with impunity, as the United Nations whitewashes their actions. When a high-level UN whistleblower named Anders Kompass came out publicly about the crimes, the UN did everything in its power to discredit him and make his life unbearable, rather than address the crimes. There are many more, but these examples should suffice to show why Sachs’ globalist plan is doomed to fail: Sachs believes that the United Nations, one of the most irredeemably corrupt organizations in the world, an organization that is larded with dictators and human rights abusers, will actually work diligently toward the goal of the betterment of man — and not toward the goal of the betterment of UN insiders. Naïve, to say the least — and that’s not even considering the rampant corruption in the aid-receiving countries. Sachs’ plan is socialism writ large — funneling money and power into a centralized governing entity to take care of the world’s problems — but he doesn’t see how his plan would assuredly end up following the same failure as past socialism, such as that which caused economic devastation in Venezuela, the Soviet Union, North Korea, Zimbabwe, and more. When a centralized governing entity is given the power to do good, it is also given the power to do bad, and under socialism the people don’t have the power to right wrongs when they occur. In fact, nearly the entire continent of Africa went the socialist route after the countries were freed from colonialism, and the result was that the GDP of the continent went down, not up, over the following dec-ades — with corruption becoming among the worst scourges. Sachs’ plan shouldn’t be surprising, because he doesn’t see socialism as bad. He seems to assume that socialism is only bad for countries because socialism limits the countries’ willingness to trade. He says socialist countries become so protectionist that they strangle themselves economically — their one main downfall, according to him. Variants on the Mainstream Plan Other people who want to “fix” or “tweak” world poverty programs believe other adjustments are needed. Poverty specialists Francis Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins promote not just changing the aid system, but changing government systems, as well. They are co-authors of two books that are considered by many to be the progressive answers to world hunger, World Hunger: Twelve Myths (1986), and World Hunger: Ten Myths (2015). Since by-and-large their books seem to be considered the old and new testaments of something like a progressive poverty bible, and likely reflect the thinking of a sizable number of so-called progressives, they deserve some exploring. To remedy the decades-long failures of international aid, Lappé and Collins say that along with more “democracy” in government, the world needs an “expansion of basic human rights. They [the rights that the duo want] include education (particularly for women) and economic opportunity, as well as access to food, health care. And contraception.” A primary contention of theirs is that because private corporations have too much control of the world, people go hungry, so the people must be empowered to save themselves. They add that the world, even the Third World, produces enough food to feed everyone. Outside of the United States, about 30 percent of the people are obese or overweight — but the food isn’t getting fairly distributed and the poor don’t get their share, and the poor are being cheated out of land and opportunities to get ahead. Though the authors don’t outwardly say they are for socialism as a solution, that’s what their plans amount to. The authors do offer a couple options for success against poverty without greatly enlarging the power of governments, but that prohibition doesn’t last. Briefly they refer to redirecting government aid to fix apparent problems, instead of growing government. They say we should cut back on subsidizing beef for the rich (so we don’t use so many crops to feed animals) and use those monies to convince people not to eat meat (this is supposedly to reduce the costs of food for the poor by making more grains available to them, though this is basically illogical because recent years have seen worldwide grain gluts to the extent that all the grain grown can’t be consumed). For the same reason, they want to reduce wasted food (as if people don’t try to keep their food from rotting and not waste money). They are also adamant that farm yields in poor countries can be increased merely by abandoning the idea that modern Western agricultural practices will help the poor and by training the poor to more intensively grow crops on very small parcels of land and by doing things such as growing trees amid the crops, since tree-growing makes crops less susceptible to drought, and certain trees fix nitrogen in the soil. They call their plan “agroecology.” But the rest of their suggestions rely on large, powerful, benevolent government — as if that is easy to achieve, or even ever achievable. First, the authors want poor countries to store food for when famine happens, and for governments to make food a human right: “Since food is both necessary to life itself and a market commodity, the only way this right can be realized is if democratic government ensures that every person has the means to secure enough healthy food through access to employment at a living wage; or, if blocked from paid employment by old age, ill health, or family responsibilities, one has access to public support.” Next, the authors require that electric power be provided by “green energy” (which would literally cover the Earth with solar panels and wind turbines, and would be hardly good for the Earth, and would only provide intermittent power — because neither the sun nor the wind stick around). And they demand that the world get rid of most pesticides and synthetic fertilizers and their costs, as well as genetically modified seeds, while having communities take control of local resources such as land (redistributing land), instead of individuals owning the resources. (The authors deride big landowners, saying that they have access to more land simply because they are rich, rapacious, and powerful, and since all they care about is profits: “Many big growers often overuse the soil, water, and chemical inputs, thoughtlessly eroding the soil, depleting the water, and poisoning the environment.”) Finally, they want to end the trade preferences given to powerful Western countries through the WTO and multinational trade treaties because the trade preferences allow Western governments unfair advantages in trade over Third World ones, keeping the poor destitute. While the authors might have a valid point in their criticisms of how the world trade system is rigged against Third World countries, the remainder is a case of wishful thinking: asserting as true what they want to be true — planning for wonderful results from socialism despite its horrific track record, and expecting altruistic good deeds from governments that have up to now continuously shortchanged and abused the poor. To achieve their goals, they claim what is needed is “a particular kind of government: What we call a Living Democracy, engaging citizens and accountable to them.” Though the authors deny they want drastically empowered centralized government, implementation of their plans would require centralized, massively powerful government to make it happen. Consider that governments would need to seize private property to be able to redistribute it; governments would need to control all facets of work in order to guarantee employment at a living wage (communism, anybody?); and governments would have to be vested with the power to create and destroy rights in order to expand rights to include education, economic opportunity, food, healthcare, and contraception. The flaws are obvious, except to someone who can’t see the forest through the trees. First, if a person must ask permission of government to do something, it’s not really a right, and when property is taken from someone to redistribute to others, it is theft. Second, since there is no way that any Third World country can afford any of the main initiatives, governments would have to try to force some of their people to provide services for free — or at least provide them for less than the services or goods cost to provide them — or have First World countries foot the bills. (All of the authors’ solutions represent hardcore socialism and are doomed to fail just as surely as are all price-control schemes, such as those that are causing mass starvation in Venezuela at the present time.) Third, even if the governments managed to benevolently use their powers to redistribute wealth, not rampage over people, and instead allow democracy in all facets of life — as in the authors’ proposed Living Democracy — majorities of voters would merely be empowered to tell the minority what to do. That is hardly in line with citizens having real rights or autonomy or personal empowerment, and hardly different in behavior from the present, abusive Third World governments. Finally, African countries have been socialist from the start of their independence from colonial powers, and have had the ability to do all of the above, but instead have inflicted poverty, starvation, and rigid controls on their populaces with the power they were granted. Unless the two authors are thinking about having a Western army invade every poor country in the world to install citizens- and rights-friendly governments — something that, by the way, has recently already failed in Libya, Afghanistan, and Iraq — there’s no way any of this is happening. The plan is Marxist fantasy to its core, considering that once governments gain near-total control over populaces, they rarely readily give up that power. Ironically, the authors say that “concentrated power — whether public or private — undermines freedom and leads to the death of effective markets.” How right they are. To find out a genuine solution to world poverty, see our article on page 25.Photo credit: AP Images

JBS Member or ShopJBS.org Customer?

Sign in with your ShopJBS.org account username and password or use that login to subscribe.

Subscribe Now

Subscribe Now

- 24 Issues Per Year

- Digital Edition Access

- Exclusive Subscriber Content

- Audio provided for all articles

- Unlimited access to past issues

- Cancel anytime.

- Renews automatically

Subscribe Now

Subscribe Now

- 24 Issues Per Year

- Print edition delivery (USA)

*Available Outside USA - Digital Edition Access

- Exclusive Subscriber Content

- Audio provided for all articles

- Unlimited access to past issues

- Cancel anytime.

- Renews automatically