Today, on the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which declared segregated public schools unconstitutional, one might try asking anyone heard praising that historic decision if he or she has ever read it. Chances are any verbal reply will be preceded by a blank stare. Americans, for the most part, don’t actually read those rulings that our highest court says are required by our Constitution, any more than we read the Constitution. We just decide whether we like or dislike what a court ruling requires and take sides accordingly, continuing to either praise or damn a Supreme Court decision long after the finely honed or fantastically spun legal arguments on either side have been forgotten. Brown enjoys nearly universal praise today because we rightly find morally repugnant the practice of categorizing and assigning people by race. We give little, if any, thought to the question before the Court, which was whether school desegregation was required by the 14th Amendment mandate that each state provide to all persons the “equal protection of the laws.” Nor do we tend to give much thought to how the ruling affected the constitutional balance between federal and state powers and how the Court’s interpretation of the 14th Amendment has led to vast claims of judicial powers over the life of the nation likely undreamed of by the framers of the Amendment.

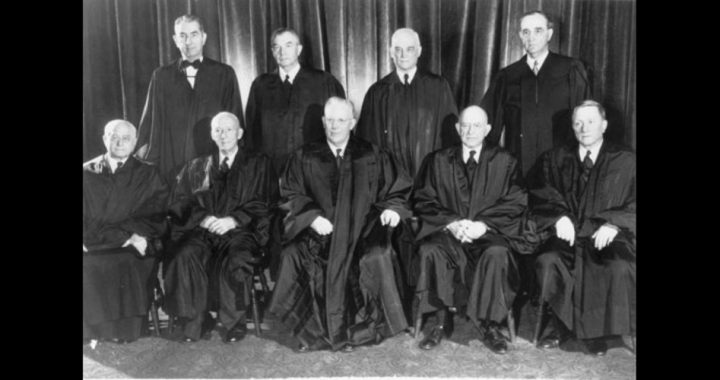

Neither the revered status of the decision today nor the fact that it was a unanimous 9-0 ruling of the Court (shown) should cause us to forget how controversial Brown was when it was announced on May 17, 1954. Though Southern segregationists cried the loudest, legal arguments could be found on both sides of the Dixon line that in overturning the “separate but equal” standard established in the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of 1896, Chief Justice Earl Warren and his brethren issued a ruling that was more a sociological treatise than a legal opinion.

Writing for the Court, the Chief Justice noted the lower courts’ findings that “the Negro and White schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other ‘tangible’ factors.” The plaintiffs based their case instead on an intangible factor, arguing that segregated schools imposed on the black children the stigma of inferiority, which had a negative effect on their ability to learn. The Court agreed, based on dubious “modern authority,” referenced in a footnote to Warren’s opinion. One source was a study done by Kenneth Clark, a social psychologist at City College of New York. Clark had testified in trial court about a series of tests he had conducted, demonstrating that black children preferred white rather than black dolls. Also cited, by title only, were several studies on the psychological and sociological effects of segregation, including An American Dilemma by Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal.

The Chief Justice spent little time and printer’s ink on the question of whether the Congress that passed the 14th Amendment or the states that ratified it had intended thereby to outlaw segregation in the public schools. “In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868 when the Amendment was adopted or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written,” Warren wrote. “We must consider public education in light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.”

With that breezy dismissal of the intention of the lawmakers, Warren cleared the deck for the Court to impose its own enlightened understanding of what was needed in the public schools. To have spent any more time on the history of the Amendment and the way it was understood at the time of its passage might have required acknowledgment of the fact that the same Congress that passed the Amendment also established segregated schools in the District of Columbia, and that the majority of states ratifying the amendment either had segregated schools at the time or established them soon after.During Reconstruction, the Freedmen’s Bureau, established by Congress, set up segregated schools throughout the South. The “separate but equal” rule had been upheld time and again in the decades since the Plessy ruling, including a unanimous Supreme Court ruling (Lum v. Rice) in 1927, in which Chief Justice William Howard Taft wrote that the principle left the matter “within the discretion of the State in regulating its public schools and does not conflict with the 14th Amendment.” As noted by the 101 members of Congress who signed the declaration known as the “Southern Manifesto,” racially segregated schools had been established in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and other Northern states, where the practice continued “until they, exercising their rights as States through the Constitutional process of local self-government, changed their school systems.”

Section 5 of the Amendment assigns to Congress, and not the courts, the power to enforce its provisions. Congress had never outlawed segregated schools and as late as 1946 had, in legislating grants for school lunches, required “just and equitable distribution of the funds” where “a state maintains separate schools for minority and majority races.”The Brown decision also ignored the Tenth Amendment: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States, respectively, or to the people.” The Constitution nowhere delegates powers to the federal government concerning schools or education.

In ruling that segregation in schools imposed psychological harm on members of the minority race, Chief Justice Warren wrote: “Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority.” Writing in the American Bar Association Journal of April 1956, Eugene Cook and William I. Potter noted that contrary to the rules of judicial procedure, the Court had based its decision on sociological texts that had not been entered as evidence.

“Should our fundamental rights rise, fall or change along with the latest fashions of psychological literature?” they asked. Regarding the Court’s overturning of the Plessy rule based on the “psychological knowledge” of “modern authority,” H. Gifford Irion wrote in the Georgetown Law Journal: “It is impossible to read this portion of the opinion without concluding that a constitutional doctrine which had endured for fifty years was cast into limbo on the authority of sociological writings which were accepted as beyond dispute.”

Had the Plessy precedent been upheld, would schools in the South still be segregated today? It seems unlikely. Notwithstanding the Southern resistance to (in the words of the Southern Manifesto) “outside agitators … threatening immediate and revolutionary changes in our public school systems,” attitudes were changing and racial barriers had been falling before the Brown decision. Georgia had eliminated its poll tax in 1945, removing a barrier to black voting. The military had been desegregated by order of President Truman. The Red Cross had eliminated racial designation of blood donors. Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color barrier in 1947, and in the decade that followed black and white teammates became the rule rather than the exception. Black performers were playing a greater part and gaining increased visibility in the entertainment industry. With the advent of rock ‘n’ roll, black and white teenagers were buying the same records and dancing to the same music. And it’s possible that the cost of “equalizing” black and white schools, added to the duplicative costs of simply maintaining a dual school system, would have forced states to desegregate for economic reasons.

Instead, Brown became the first of the Warren Court’s many rulings that vastly expanded the power of the federal judiciary over the states. Soon the Supreme Court altered its interpretation of the 14th Amendment to require the assignment of children to schools based on race in order to achieve what the courts had determined to be a proper “racial balance.” That in turn required the busing of children away from neighborhood schools to distant locations, igniting a backlash among parents, North and South, that brought back memories of Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. In the years following the Brown decision, the Court used the 14th Amendment to carry out a revolution in constitutional law, outlawing prayer in public schools, ordering the redrawing of legislative districts to meet a “one man-one vote” mandate, overturning obscenity laws, and striking down a state law banning the sale of contraceptives, to cite but a few examples. The trend would continue post-Warren, with the Court under Chief Justice Warren Burger ruling that an undefined — indeed, unmentioned — right to privacy in the U.S. Constitution required the striking down of state abortion laws and the substitution of a new law for all 50 states, improvised by the Court itself. In dissenting Justice Byron White’s protest against “the exercise of raw judicial power” in Roe v. Wade, one might hear an echo of the Southern Manifesto’s charge that the Brown decision was “bearing the fruit always produced when men substitute naked power for established law.”

However morally repugnant the practice of segregating people by race was and is, the signers of the “Southern Manifesto” delivered to the nation a fair and prophetic warning: “We appeal to the States and the people who are not directly affected by these decisions to consider the constitutional principles involved against the time when they, too, on issues vital to them, may be the victims of judicial encroachment.”

Photo of the Warren Court that ruled in Brown v. Board of Education with Chief Justice Earl Warren at front, center