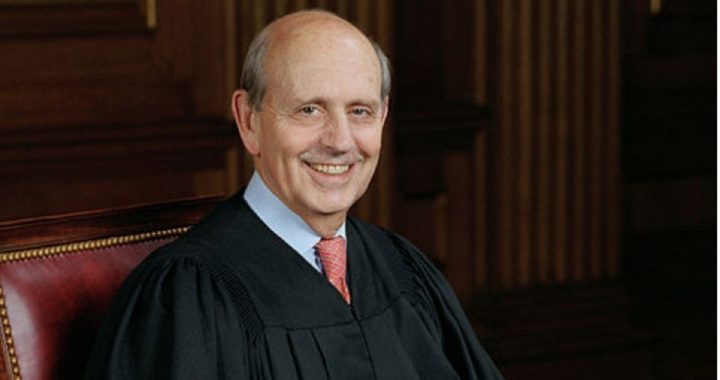

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer’s new book, The Court and the World: American Law and the New Global Realities, is the latest salvo in the continuing war to destroy the independence of the United States.

The New York Times noted,

[The book] will reignite the politically combustible topic of the role foreign law should play in American judicial decisions. It discusses cases in which justices have considered foreign practices and materials in their opinions. Many of those opinions concerned statutes and treaties…. But others involved the meaning of the United States Constitution, where the citation of foregn law can raise strong objections.

In 2005, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy cited decisions made by foreign courts in major gay rights and death penalty cases, prompting Justice Antonin Scalia to pen this strong dissent: “The basic premise of the court’s argument — that American law should conform to the laws of the rest of the world — ought to be rejected out of hand.”

Although all members of the Supreme Court have taken an oath to support the Constitution of the United States as the “supreme law of the land,” it appears that this oath is not being taken seriously by Breyer. The thesis of his book is that “the best way to preserve our basic values is not to ignore what goes on elsewhere [in the world], but the contrary.”

Breyer argues that in an increasingly interconnected world, it is helpful for American justices to understand what cases are occurring in other nations, whether their own cases involve national security, free speech, antitrust law, or other matters. He insists that although decisions of foreign courts are not binding on U.S. courts, they could be “instructive,” and American judges should be free to cite and apply foreign law in cases which come before them.

One issue on which Breyer believes U.S. judges could use foreign “instruction” is the death penalty. In a recent case, he argued that only 22 countries carried out executions in 2013, implying that because the United States was one of only eight nations that executed more than 10 people that year, it is out of step with the rest of the world.

In a 2005 death penalty case, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia noted that in 1788 Alexander Hamilton had assured the people of New York that they had nothing to fear from the creation of the federal judiciary, and the granting of tenure to them. Hamilton promised in The Federalist, No. 78, that there was little risk because these tenured judges would be “bound down by strict rules and precedents which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case,” and “the judiciary … has neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment.” (Emphasis in original.)

However, the recent jailing of Kentucky clerk Kim Davis for refusing to issue same-sex “marriage” licenses demonstrates that Hamilton was far too sanguine in his contention that the judiciary has only judgment, but not force or will.

Scalia noted that death penalty opponents on the High Court such as Breyer like to cite the views of the “so-called international community,” but consider the views of American citizens “essentially irrelevant.”

In the 2005 case, Scalia’s dissent decried the use of foreign law by U.S. federal judges. He condemned the citation of “Article 37 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which every country in the world has ratified save for the United States and Somalia.” The UN article contains an “express prohibition on capital punishment for crimes committed by juveniles under 18.”

Scalia then declared: “Unless the Court has added to its arsenal the power to join and ratify treaties on behalf of the United States, I cannot see how this evidence favors, rather than refutes, its position.” Since the U.S. Constitution explicitly states that only those agreements ratified by two-third of the Senate are considered law in the United States, the fact that the Senate has not so ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child means that it is not law in the United States.

Breyer’s book is a bold assertion that U.S. law, including the Constitution itself, should be interpreted in the light of the law and practice of other nations. For instance, he insists that it is “highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment.”

Breyer is not alone in advocating the use of foreign law in U.S. federal courts. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has asserted that she “prefers” the Constitution of South Africa over the U.S. Constitution. And a decade ago, Justice Anthony Kennedy cited decisions from foreign and international bodies in “gay” rights and death penalty cases.

Breyer, Ginsberg, and Kennedy are quick to see wisdom in the decisions of foreign judges, but as Scalia declared, “It is interesting that whereas the Court is not content to accept what the States of our Federal Union say, but insists on inquiring into what they do, the Court is quite willing to believe that every foreign nation — of whatever tyrannical political makeup and with however subservient or incompetent a court system — in fact adheres to a rule of no death penalty for offenders under 18.”

Scalia noted many cases in which the liberals on the Supreme Court do not make any use of foreign laws, but are actually very selective. “The laws of most other countries differ from our law,” he asserted, “including not only such explicit provisions of our Constitution as the right to jury trial and grand jury indictment, but even many interpretations of the Constitution prescribed by this Court itself,” giving the “exclusionary rule” as an example. (The exclusionary rule holds that evidence collected in violation of the defendant’s constitutional rights is sometimes inadmissable for a criminal prosecution in a court of law.) This rule has been “universally rejected” by other countries, said Scalia, and the “European Court of Human Rights has held that introduction of illegally seized evidence does not violate the fair trial requirement” found in the European Convention on Human Rights.

Scalia charged that another area in which the Court has ignored how the rest of the world does things is in their interpretation of the First Amendment’s “Establishment Clause.” Most other countries “do not insist on the degree of separation between church and state that this Court requires,” he explained, citing the examples of the Netherlands, Germany, and Australia, which actually “direct government funding of religious schools,” adding that England even permits the teaching of religion in its state schools. “And let us not forget the Court’s abortion jurisprudence,” Scalia continued, “which makes us one of only six countries that allow abortion on demand until the point of viability.” He added that other nations do not bother with prohibitions against double jeopardy in criminal cases, and that jury trials are not standard in the rest of the world.

“To invoke alien law when it agrees with one’s own thinking, and ignore it otherwise, is not reasoned decision-making, but sophistry,” Scalia concluded.

During George W. Bush’s presidency, he ordered the state of Texas to obey a decision of the World Court and refrain from executing a convicted rapist and murderer. Texas took the position that neither Bush nor the World Court had any jurisdiction over the criminal statutes and practices of the Lone Star State, and defeated the Bush administration at the Supreme Court. Though it was a positive step for national and state sovereignty, the fact that such a case even had to be fought in court should be alarming.

Constitutionalists recognize that those who favor the use of foreign law and the decisions of foreign judges as a basis for American law, regardless of the clear wording of the Constitution to the contrary, are moving America closer to a world government.

This book by Stephen Breyer, a judge on the Supreme Court — proposing that foreign law should (at least in some cases) trump U.S. or state law and even the U.S. Constitution — should awaken Americans to the dangers of the loss of their national independence.

If a majority of the members of Congress were truly dedicated to preserving America’s sovereignty, they would impeach those judges who openly ignore their oath to the U.S. Constitution.

Steve Byas is a professor of history at Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College in Moore, Oklahoma. His book, History’s Greatest Libels, is now available.