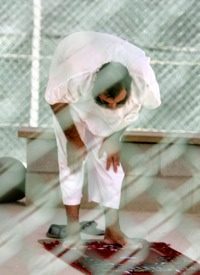

Yasser al-Zahrani and Salah al-Salami, of Saudi Arabia and Yemen respectively, allegedly committed suicide in 2006 while in American custody at the infamous prison. Although the cause of death is the subject of dispute in the current litigation, a report issued by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) found that the deaths were the result of suicide by hanging.

On January 7, 2009, families of the two former detainees filed a complaint in the federal district court naming as defendants the United States and more than a score of officials of the government, including Donald Rumsfeld. The suit alleges that the named government officers were responsible for subjecting the decedents to torture, arbitrary detention, and ultimately, wrongful death.

The district court dismissed the complaint pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted.

An appeal of that decision was brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and was heard by the D.C. Appeals Court. Writing for the unanimous court, Chief Judge David B. Sentelle (a Reagan appointee) upheld the lower court’s ruling, stating that “Congress has expressly deprived the federal courts of jurisdiction over cases like the one before us.”

Specifically, Judge Sentelle explained that

the federal courts are courts of limited subject-matter jurisdiction. For a case or controversy to fall within the authority of an inferior court created under Article III of the Constitution, the Constitution must have supplied to the courts the capacity to take the subject matter and an Act of Congress must have supplied jurisdiction over it.

And, further:

In October of 2006, Congress enacted the Military Commissions Act [MCA]. Section 7 of the MCA included an amendment to the habeas corpus statute. The amended statute reads:

(1) No court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider an application for a writ of habeas corpus filed by or on behalf of an alien detained by the United States who has been determined by the United States to have been properly detained as an enemy combatant or is awaiting such determination.

(2) Except as provided in [section 1005(e)(2) and (e)(3) of the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005], no court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider any other action against the United States or its agents relating to any aspect of the detention, transfer, treatment, trial, or conditions of confinement of an alien who is or was detained by the United States and has been determined by the United States to have been properly detained as an enemy combatant or is awaiting such determination. 28 U.S.C. § 2241(e)(1) and (2).

The present litigation rather plainly constitutes an action other than habeas corpus brought against the United States and its agents relating to “aspect[s] of the detention … treatment … [and] conditions of confinement of an alien” as described in the MCA. Therefore, as the District Court noted, this action is excluded from the jurisdiction of this court by the “plain language” of an Act of Congress. This ends the litigation and requires that we affirm the dismissal of the action.

And, finally, the ruling addressed the applicability of the earlier case of Boumediene v. George W. Bush, in which the U.S. Supreme Court held that the suspension of habeas corpus contained in the Military Commissions Act was unlawful and that all habeas corpus petitions stayed by that law were eligible to be reconsidered and reinstated.

We further hold that the Supreme Court did not declare [MCA] unconstitutional in Boumediene and the provision retains vitality to bar those claims. We therefore conclude that the decision of the District Court dismissing the claims should be affirmed, although for a lack of jurisdiction under Rule 12(b)(1) rather than for failure to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6).

According to published reports, al-Zahrani hanged himself using bed sheets and articles of his own clothing.

In February 2010, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia granted the defense’s motion for dismissal. Later, that same court denied a motion for reconsideration filed by the plaintiffs after they came into possession of theretofore unknown eyewitness accounts from military guards suggesting that the men died while being tortured by interrogators.

The judge justified his ruling by pointing out that such evidence does not change the fact the “special needs of foreign affairs must stay” the court from reaching any other conclusion.

Originally, the plaintiffs argued the Alien Torts Claim Act, which grants original jurisdiction to the federal district courts to hear claims for injuries “committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.”

The defendants’ motion to dismiss cited Section 7 of the Military Commissions Act, which removes from the federal courts jurisdiction in matters dealing with the treatment of persons “properly detained” as enemy combatants.

One relevant consideration, and one left unaddressed by the court in this case, is whether this provision of the MCA is an unconstitutional bar to cases, such as the present one, seeking to enforce constitutional rights.

The closest the D.C. Appeals Court comes to directly confronting this issue is in the following statement:

The only remedy [plaintiffs] seek is money damages, and, as the government rightly argues, such remedies are not constitutionally required. The Supreme Court has made this eminently clear in its jurisprudence finding certain of such claims barred by common law or statutory immunities, and applying its “special factors” analysis in preclusion of Bivens claims.

In the case of Bivens v. Six Unknown Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971), the Supreme Court unanimously held that “bedrock principles of separation of powers dictate that the judiciary refrain from implying a remedy when special factors counsel hesitation in the absence of affirmative action by Congress.”

If Congress makes a designation such as the one known as “enemy combatant,” then that is one of the “special factors” that judiciary should not undo by permitting lawsuits that challenge the authority of Congress to make such designations. Simply put: If Congress did it, then only Congress can undo it.

As usual, the commentators contributing to the Lawfare blog have posted an astute examination of this ruling:

The problem with such analysis is that the Supreme Court has never, in fact, squarely held that damages remedies for constitutional claims are never constitutionally required. To the contrary, with one equivocal exception, every decision the Court has handed down in the Bivens context has presented a scenario where at least some remedy was available in some other forum — where the choice was not “Bivens or nothing.” And in other non-habeas contexts, the Court has gone so far as to suggest that there may be circumstances in which the Constitution does require a remedy (from which it should follow that the remedy would be damages when no other alternatives were available).

Conveniently, the investigators from the NCIS reported discovering notes written by al-Zahrani and al-Salami declaring their intent to become martyrs. The military immediately stonewalled all efforts by civilian groups to perform independent investigations into the deaths.

Similar requests filed by the governments of Yemen and Saudi Arabia were rejected by military officials in charge of the investigation.

The most compelling question left unanswered is whether the American people will sit idly by and permit such gross misinterpretations of the Constitution and habitual denials of habeas corpus when the names of those suffering torture and indefinite detention change from Yasser al-Zahrani and Salah al-Salami to John Smith and Joe Brown.

Photo: AP Images