Special Counsel Robert Mueller has been digging into alleged connections between President Trump and Russia since May. In late October, his investigation resulted in the indictment of Trump associate Paul Manafort. Now, former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn has pled guilty to “willfully and knowingly” making “false, fictitious and fraudulent statements” to the FBI regarding conversations with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak. Trump’s enemies in politics and media are touting this as evidence of Trump/Russia collusion. But is it?

Retired General Michael Flynn served as President Trump’s national security advisor for less than one month — from January 20, 2017 to February 13, 2017 — before he was forced to resign after it became clear that he had lied to FBI investigators about his contacts with Kislyak during the transition.

Almost as soon as Flynn agreed to a plea deal for the charges against him, the liberal media went into high gear, pumping out article after article and program after program claiming that this was proof of collusion. ABC’s Brian Ross got a little ahead of the pack and reported that Flynn had reached out to Russian representatives while Trump was still a candidate. In reality, the four conversations Flynn has admitted to lying about all took place during the transition period between the election and the inauguration — at a time when presidents-elect customarily have their people reach out to other nations. And while Ross — who has been suspended without pay for four weeks — was on the far end of the spectrum, he was not leaps and bounds ahead of others.

When Obama levied sanctions against Russia in the waning days of his presidency, it created a situation-in-waiting for Trump as the incoming president. Inheriting bad U.S./Russia relations was not a pretty prospect. Incoming National Security Advisor Flynn urged Russian Ambassador Kislyak during a December 29, 2016 phone call “to refrain from escalating the situation.” In a subsequent call, Kislyak told Flynn that Moscow had “chosen to moderate its response to those sanctions as a result of [that] request.”

Let’s unpack that. Obama — apparently peeved that his party’s candidate lost and in a move that seems designed to lend false credibility to allegations of Trump/Russia collusion — tossed a grenade (or in this case, a Molotov cocktail) over his shoulder on his way out by issuing sanctions against Russia. The Trump transition team acted to defuse that grenade and diffuse the situation. The act of Flynn calling Kislyak to ask that Moscow not to overreact to Obama’s pointed insult is not collusion; it is good relations.

Of course, not all of Flynn’s communications with Kislyak were a matter of cleaning up behind Obama’s sore-loser tantrum; the week before Obama imposed those sanctions, Flynn had spoken to Kislyak about a pending UN resolution. Flynn had asked the ambassador to either delay the vote on that resolution or see if he could help defeat it. Flynn and Kislyak spoke later about that same resolution and Russia’s response.

Flynn — who, as an agent of a foreign power due to his lobbying, was subject to monitoring under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) — seems not to have been aware that his calls were being recorded by the FBI. On January 24, 2017, Flynn denied all four of those communications. Within days, President Trump demanded Flynn’s resignation.

As Mueller’s investigation approached its seventh month with little more to show for it than an indictment of Paul Manafort for charges unrelated to (and predating) allegations of Trump/Russia collusion, Mueller appears to have cranked up the heat on Flynn enough to get a plea deal. This — again — is a long way off the mark of proving that Trump is (in Hillary Clinton’s words) Putin’s puppet. All it proves is that when a man who is caught red-handed lying to FBI investigators is given the choice between a possible five-year sentence if he is found guilty and a six-month plea deal, the math is easy.

Mueller charged Flynn for one count of “willfully and knowingly” making “false, fictitious and fraudulent statements” to investigators. All four of his lies were listed in that one count.

To put it in the for-what-it’s-worth column, no one is credibly claiming there was anything illegal in Flynn’s communications with Kislyak. Where Flynn saw problems was when he lied to investigators. Had he told the truth, he would have been fine. Lying to investigators often results in being charged. Of course, there is the chance that the person lying to investigators is named Clinton and the subject is sending and receiving thousands of classified e-mails over a unsecured, unauthorized, private server and account — and deleting more than 30,000 e-mails while claiming everything was turned over to investigators. In that case, it appears not to be a crime at all.

Since Flynn’s crime — his only crime — in all of this was in lying about it, and Trump demanded his resignation for that and then publicly said that was the reason, Flynn’s plea is not an indictment of Trump; quite the opposite — it shows that Trump acted appropriately.

Flynn’s guilty plea for lying also creates a situation for Mueller that as good as proves that the special counsel has no solid evidence of collusion: Admitted liars make lousy witnesses and Flynn has agreed to cooperate with Mueller’s investigation as part of the plea deal. As a result, it may matter little whether Flynn put the finger on anyone connected to Trump.

So, while time will tell what Mueller comes up with next, the Flynn plea deal is much ado about nothing.

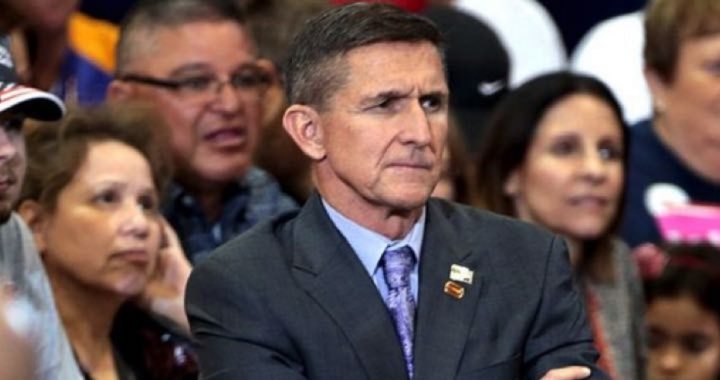

Photo of Michael Flynn: Gage Skidmore