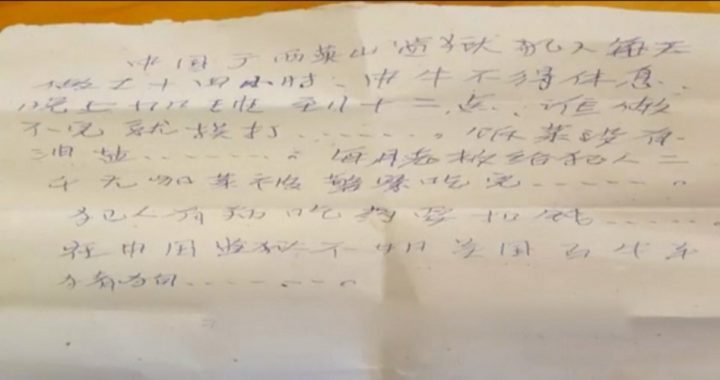

A woman shopping at a Walmart in Arizona found a desperate note (shown) apparently written by a prison laborer in China pleading for help. The woman, identified as Laura Wallace, said she found the note, written in Chinese, hidden inside the compartment of a purse purchased at a Walmart in Sierra Vista.

Fox News reported that the note, which Wallace said was translated independently by a number of people fluent in Chinese, read as follows: “Inmates in the Yingshan Prison in Guangxi, China are working 14 hours daily with no break/rest at noon, continue working overtime until 12 midnight, and whoever doesn’t finish his work will be beaten. Their meals are without oil and salt. Every month, the boss pays the inmate 2000 yuan, any additional dishes will be finished by the police. If the inmates are sick and need medicine, the cost will be deducted from the salary. Prison in China is unlike prison in America, horse cow goat pig dog [meaning prisoners are treated inhumanely].”

Wallace emphasized that she was sure the note came from a prisoner in China, relating “what their situation was and how they work long hours, 14 hours a day. And they don’t have a lot to eat.”

She told Tucson’s KVOA news that “I don’t have the means or the access to help in any way. So I think this was my way of putting in my two cents.” she added that “I don’t want this to be an attack on any store. That’s not the answer. This is happening at all kinds of places and people just probably don’t know.”

Walmart, which is a leading U.S. supplier of goods manufactured in communist China, said in a statement: “We can’t comment specifically on this note, because we have no way to verify the origin of the letter, but one of our requirements for the suppliers who supply products for sale at Walmart is all work should be voluntary as indicated in our Standards for Suppliers.”

According to USA Today, Li Qiang, executive director of the advocacy group China Labor Watch, said that “most … Walmart supplier factories in China have very poor labor conditions.” The national news site quoted Walmart spokesperson Ragan Dickens as saying that the retailer is “making contact with the customer and appreciate her bringing this to our attention. With the information we have, we are looking into what happened so we can take the appropriate actions.”

Nonetheless, the discount giant subtly conceded the possibility that worker abuse continues to occur within its global supply chain. “Our ability to find qualified suppliers who uphold our standards, and to access products in a timely and efficient manner, is a significant challenge, especially with respect to suppliers located and goods sourced outside the U.S.,” the company said in a statement reported by USA Today.

This is not the first time such desperate pleas have found their way out of Chinese prison labor camps. In September 2012 a New York City woman reportedly discovered a note pleading for help inside a shopping bag she purchased at Saks Fifth Avenue. The writer of the note was later identified as Tohnain Emmanuel Njong, from Cameroon, who was imprisoned in the city of Qingdao at the time he wrote it. The note read in part: “We are ill-treated and work like slaves for 13 hours every day producing these bags in bulk in the prison factory.” Njong was released in December 2013.

And in October 2012 a woman in Oregon found a similar plea for help inside a box of Halloween decorations she purchased at a local Kmart. The letter asked that someone notify the World Human Right Organization: “Thousands people here who are under the persecution of the Chinese Communist Party Government will thank and remember you forever.”

In 2013 a 47-year-old Chinese national identified only as Zhang told the New York Times that he had penned the Kmart letter while he was a prisoner in the Masanjia labor camp in Shenyang, recalling that it was one of a score of such notes he secretly penned while serving a two-year sentence. “For a long time I would fantasize about some of the letters being discovered overseas,” he told the Times, but over time I just gave up hope and forgot about them.”