At a Newseum event in Washington on January 12, someone asked Senate Judiciary Chair Patrick Leahy, “In the wake of [the mass shooting in Tucson] last weekend, do you think there should be more talk about gun control and do you foresee any legislative push for that on Capitol Hill?” Leahy responded, “There will be, but I don’t know if much will change it.”

The Democratic Senator from Vermont also observed:

Vermont has the lowest crime rate in the country, lowest or second lowest, and doesn’t have gun control. But I would not want Vermont laws to be in an urban area. We have to decide what works best.

Vermont has perhaps the least restrictive gun laws in the nation. There is no requirement to register a gun, no license needed to purchase a gun, no permit needed to carry a concealed handgun — almost no regulation at all on the ownership of guns. Interestingly, Vermont also has the lowest violent crime rate in the nation: 137 per 100,000, compared with the national average of 457 per 100,000. Second Amendment supporters see a connection between those two facts.

Self-defense is one purpose for the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and it is also a purpose stated in the Vermont Constitution — in fact, self defense was the original basis for the right to bear arms in the state. Article 16 of the Vermont Constitution specifically states: “The people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and the State.”

Another purpose of the Second Amendment is to prevent official oppression, and Vermont has a storied history of using firearms to protect liberty. During the American War of Independence, when General Burgoyne was attempting to bisect the colonies by a push through New York, a key battle (though not a large one) was fought near Bennington, Vermont. Folk music records what Vermonters responded to British soldiers who would impose their will upon them:

Why come ye hither, Redcoats? Your mind what madness fills? For there’s danger in our valleys and there’s danger on our hills. Why hear ye not the singing of the bugle wild and free? Full soon you’ll hear the ringing of the rifle from the tree! For the rifle, for the rifle: in our hands shall prove no trifle.

There are other important historical facts about the Green Mountain State. Vermont considered itself an independent nation for some time. When the U.S. Constitution was adopted, Vermont was not a state; it was disputed land between New York and New Hampshire. (Interestingly, Maine too was not a state at that time, but rather a part of Massachusetts — a bit of trivia often lost on American students today.) Vermont considered itself an independent republic for 14 years before acceding to join the United States — after respectfully disagreeing with its neighbors that it was part of another state, and showing a willingness to support that opinion with its armed militia. When Vermont then joined the Union — slavery having already been banned — it entered as a completely free state.

This sense of independence is still alive in the hearts of Vermonters. In November 2005, a convention of more than 400 citizens met in the State House, and after a day of debate passed a resolution of independence (essentially secession). The objection was that the nation had only a one-party rule under President George W. Bush. The resolution stated:

Be it resolved that the State of Vermont peacefully and democratically free itself from the United States of America and return to its natural status as an independent republic as it was between January 15, 1777 and March 4, 1791.

This new proposed polity, the Second Vermont Republic, considered also seeking provincial status in Canada. The movement continues, and it defies simple ideological classification — blending a love of ecology with ideals which constitutional conservatives would support, such as small government and individual liberty, and a wariness of the CIA, for instance.

Vermont has also preserved citizen government by maintaining the old system of town hall meetings. In fact, Town Hall Day is an official state holiday. Without professional politicians, Vermonters decide the budget of their community, choose its officers, and so forth. In spite of the Far Left politicians who have come out of Vermont in recent years, its citizens seem to like small government close to the people. Those familiar with the old Newhart TV series, situated in a small, mythical town in Vermont, will recall that in one episode a townsman approached the citizen-mayor after that official was obliged to take some government action, and blurted out to him: “But the only reason we elected you was that you promised not to do anything!”

Vermont has been different in other ways. After admission to the United States, the state remained one of the few that did not provide for the popular election of presidential electors. These electors were instead chosen by the Vermont Legislature, reserving sovereign prerogatives for the State of Vermont itself. All states now provide that the presidential electors are chosen by the people, leading to the incorrect assumption that the U.S. Constitution somehow makes that provision. In fact, as the Florida Legislature briefly reminded the world during the shenanigans after the 2000 presidential election, a state legislature today could remove from the people the right to choose presidential electors and assume that power to itself.

That sort of independence has marked the history of Vermont — an independence based upon many rights: the inherent right of states to join or to leave the Union, the right to outlaw slavery, the right of free men to use rifles to resist tyrannical authority, the right to a small government built around local town halls of citizens, and to states’ rights in general. So how can Vermont send to the U.S. Senate its only formally “socialist" member? How can this be, when Vermont preserves gun-owners’ rights more scrupulously than any other state?

One must look beyond conventional understandings of “liberal” and “conservative” to answer that question.

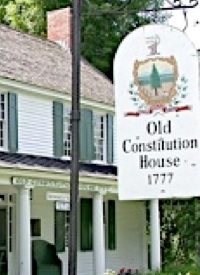

Photo: The Old Constitution House in Windsor, Vermont